THE MURDER OF JAMES DIGGLES

THE GRAVESTONE OF JAMES DIGGLES AT ST. MATTHEW’S CHURCH, RASTRICK

INTRODUCTION

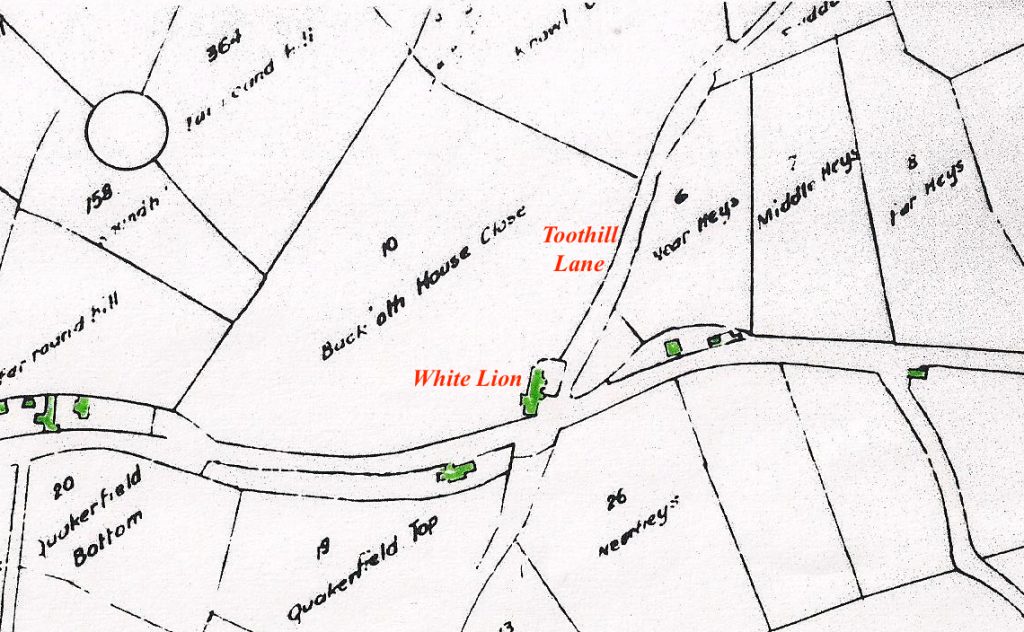

This is the story of an incident that took place almost 200 years ago at Toothill Lane, Rastrick, a road that is now named Toothill Lane South and runs from Clough Lane almost in an east/west direction, down the side of the Four Sons Inn, a hostelry which has previously been called the Clough House Inn and the White Lion Inn.

It is hard to believe but this narrow road, known locally as New Dick, was once a major highway in the 17thcentury which formed part of the Chester to London road. It travelled to the top of Toothill Bank where the road split, with one road leading down the hill to Rastrick Common and over the River Calder before heading out towards Dewsbury whilst the other road forked off to the right and headed down Shepherds Thorn Lane, across what is now Bradley Road then down Old Road to Deighton and into Huddersfield.

New Dick was dissected by the M62 motorway in the 1970’s and therefore it now comes to a dead end but a public footpath travels across an adjacent field and passes over the M62 motorway via a footbridge before re-joining the old track which then continues its original course to Toothill Bank.

It was in this area that our story takes place and involves two groups of local men who had an altercation in the White Lion. It resulted in the death of James Diggles, following a vicious assault.

An 1824 map of Rastrick with Toothill Lane travelling between the fields named Near Heys and Back ‘Oth House Close.

A google maps satellite view of the area from above showing Toothill Lane South as it is now called travelling from Clough Lane in an easterly direction.

Our story starts with Nathan Diggles (1766 – 1839) of Rastrick who married Eunice Pearson (1769 – 1855), daughter of John Pearson of Woodhouse, at Elland St. Mary’s Church on the 25th June 1787.

The couple lived at Birds Royd, Woodhouse, Rastrick and had several children including a son named James Diggles who was born in 1790 and baptised at St. Matthew’s, Rastrick on the 7th November that same year.

James was employed as a coachman and footman for Mr. John Armitage, a merchant of Lower Woodhouse.He was well thought of by his employer for whom he had worked since boyhood. James was friends with three men by the name of John Stott, Emmanuel Brook and Enoch Garside. Brook was the gamekeeper for Mr. Armitage and Garside was employed as his assistant whilst Stott was employed as a game-keeper for Sir George Armytage Bart. of Kirklees Hall.

On the 5th November 1824, the four men had been out to check the woods for poachers and were armed with three guns. After an uneventful evening, they eventually made their way to the White Lion public house at the end of Toothill Lane (later named the Clough House and then more recently, The Four Sons), arriving at around 11pm.

They hid their guns in a holly bush, a short distance along Toothill Lane, not being allowed to take them into the public house.

Anthony Bray (20), John Bray (22), James Tiffany (21), Christopher Tiffany (19), Henry Nuttall (24), John Dyson (20), James Ellis (21) and John Dawson were already in the pub, some of them having arrived there a little after 6pm. Nuttall and Dyson were drinking together at one table whilst the other six were drinking at another table. Some newspapers of the period state that some of these men had been previously fined for poaching and therefore there would have been no love lost between them and a group of gamekeepers.

When the four gamekeepers entered the pub, they called for some ale and sat down. Soon afterwards, James Ellis was heard to be arguing with John Stott and after some words of abuse, Ellis broke Stott’s tobacco pipe. The landlord, Richard Hepworth, in an effort to separate the two factions, asked Stott and Diggles to leave the room they were drinking in and go into the bar, which they did.

As Stott was leaving the room, Ellis said he would fight Stott or any of his backers whereupon Emmanuel Brook jumped up and struck Ellis on the chest. A brawl ensued with both men falling to the floor but Brook was too strong for Ellis and he pinned him down and told him to ‘yield’. Mr. Hepworth then took Brook and Garside into the bar, away from the other men.

About 30 minutes later, the larger group, except for Nuttall and Dyson, who were still drinking at a separate table, left the pub. Some 15 minutes later, at around midnight, Stott, Brook, Garside and Diggles also left and set off walking down Toothill lane towards Toothill along the road known locally as New Dick.

Mr. Hepworth followed them for a short distance, probably anticipating that the other men were laying in wait. He observed several men standing by the holly bush at the end of Toothill Lane and watched as some of the men turned to follow the gamekeepers down Toothill Lane whilst some remained by the holly bush. A short time later, Mr. Hepworth heard a shot fired from the direction of the holly bush and then heard a voice shout, “damn them, kill them”

Stott and Garside ran away urging their two friends to do likewise but Brook and Diggles were caught and after having their guns taken from them, they were beaten with the butts and other objects before being left for dead. Diggles moved slightly at which Anthony Bray returned and struck him a further twice with the butt end of his gun and then threw the apparent lifeless body over the fence and into the lane.

James Diggles regained consciousness and staggered back to the White Lion, covered in blood from a severe head injury. He was later attended by Simeon Fryer, surgeon of Rastrick who found that James Diggles’ skull was fractured and there was a hole about ½ inch in diameter from which his brain was protruding. He said that it appeared to have been caused by the lock of a gun. Other than a few scratches, there were no other wounds on the head or other parts of his body. James Diggles succumbed to his injury and died four days later at 7pm, Tuesday 9th November 1824.

He was laid to rest three days later in St. Matthew’s churchyard.

A Coroner’s Inquest was held at the Star Inn, Rastrick on Thursday 11th November 1824 at 10am and was adjourned at midnight before recommencing the following morning, completing at 8pm.

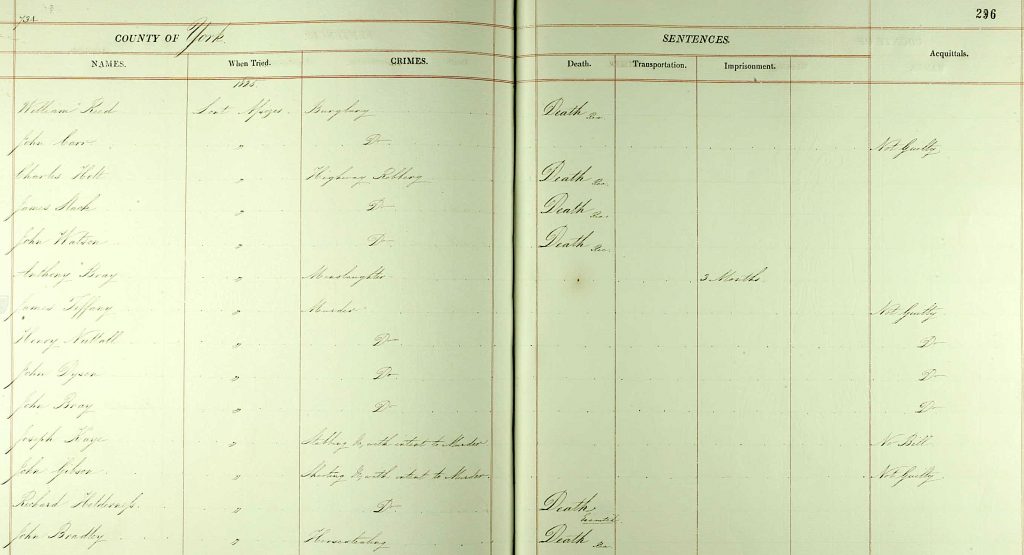

All the men involved in the incident were charged with the wilful murder of Anthony Diggles, with Anthony Bray named as the principle whilst the others were named as accomplices, aiding and abetting the murder. They subsequently appeared at Leeds Assizes on Monday, 4th April 1825

Anthony and John Bray, James and Christopher Tiffany, Henry Nuttall, John Dyson, James Ellis and John Dawson appeared before Justice Holroyd with their lives in the balance as a conviction of murder would result in them being sentenced to death.

At the trial, the landlord, Richard Hepworth described the altercation that took place in the White Lion and this evidence was followed by that of the friends of James Diggles who had been present that night.

In his evidence, John Stott said that after leaving the White Lion, he and his friends saw five of the prisoners standing by a holly bush at the top of Toothill lane and as they walked past, he heard someone say, “let’s follow them and kill them.” The prisoners then began to throw stones at the four men, who ran down Toothill lane to where they had hidden their guns in a lower holly bush. Brook and Garside recovered their guns but Brook was hit by a stone which knocked him to the ground. As he picked himself up, he fired a shot up the lane into the darkness. Although Brook was not aware of this at the time, he actually hit Anthony Bray in the head and hand, causing slight injuries.

The gamekeepers then saw several men running towards them and Stott told his friends to “run or they will kill us”. He said that Emmanuel Brook was unable to run after being hit by the stone and James Diggles refused to run saying that he had done nothing wrong. Stott and Garside ran, leaving Brook and Diggles behind.

Stott said that he and Garside ran for about 200 yards before waiting for five minutes at which point they walked back in search of their companions. They found Brook laying in the hedge-bottom of the field and with some difficulty, managed to get him back into the lane where they laid him against a wall before going back to the White Lion to obtain assistance. On his way back from the White Lion, Stott came across James Diggles who was walking towards the pub, with his head ‘much broken’ and covered in blood. He had his head tied up with a handkerchief.

Stott went on to explain that he was present when the stock of a gun was found near to where he found Emmanuel Brook. The butt end contained part of the lock which was covered in blood when found. It still had dried blood on it when it was produced in court as evidence.

Emmanuel Brook was next to give evidence and he told how James Ellis told him in the pub that he would one day kill him, by day or by night. He told of the scuffle in the bar and then went on to describe how the prisoners, except for Nuttall and Dyson, had left the White Lion. He and his friends left a short time later and as they walked down Toothill lane, they passed by some men who were standing around but no comments were made by either group. Emmanuel Brook noticed that James Ellis was amongst the men but took no notice of the others. As soon as they passed the men, they were pelted with stones, one of which hit Enoch Garside and then Brook himself was also hit in the chest. He then heard the men swear that they would follow his group and kill them. Brook said that Enoch Garside was recovering their guns from the holly bush when he was again struck by a stone which knocked him down. He was then handed James Diggles’ gun which he fired up the lane in the direction of his assailants. Despite being warned by the judge, Brook insisted that he did not point the gun at anyone in particular but just fired in that general direction. He did not look in the direction in which he fired as he feared being hit in the face by another stone. As soon as he fired the gun, he handed it to Stott, who charged it and then handed Brook his own gun.

They tried to get away by leaving the lane and crossing a field but when part way through the field, just off the lane, they heard some people in the nearby hedgerow. Stott and Garside ran away but Emmanuel Brook could not due to the injury caused by being hit by a stone and James Diggles said he would not run as he had done no wrong.

They were then caught by the other men and Anthony Bray seized Brook’s gun. At this point, Brook was hit a violent blow from behind with a hedge stake which cut through his hat and stunned him. He said that he must have been struck several times due to the bruises on his head but before being struck, he saw two of the other men seize James Diggles and take his gun from him. After the attack, he noticed the head injury that had been inflicted upon James Diggles and it was at this point that Diggles said to Brook, “I have been killed”, which was a common expression used by people who feared that they may not recover from their injuries, usually on a battlefield, not a pleasant pasture in Rastrick.

Enoch Garside told a similar story regarding the throwing of the stones by the prisoners and he told how he found a gun-stock in the lane near to where they found Brook, which he took home with him. He described how there was blood in the pan and some hairs on the dog of the lock which resembled the hair of James Diggles. In the photo to the left, the dog is the catch at the rear of the cock and one can imagine the damage it would cause if a person was struck violently about the head with this part of a gun.

Mr. Justice Holroyd told the jury that the case had properly received a very grave investigation and after all the evidence had been given, he thought that a charge of murder would be difficult to prove as that charge implied malice and in this case, it was apparent that this was an unfortunate occurrence and not a result of any previous malice. It was the result of a sudden quarrel and could not amount to anything more than manslaughter. And this could only be a charge against those prisoners who had followed the gamekeepers after the gun was fired. Only Anthony Bray had been positively identified by Brook and whilst the witnesses said that four men were involved, the jury could not convict anyone else if they could not ascertain who they were. As Emmanuel Brook was the only person to positively identify Anthony Bray, the jury had to decide whether they believed Brook’s evidence. If not, Anthony Bray should be acquitted along with the others but if they did believe his testimony, Anthony Bray should be found guilty of manslaughter.

After a few moments deliberation, Anthony Bray was found guilty of manslaughter and all the other accomplices, not guilty.

Anthony Bray received a very short sentence of just three months imprisonment.

Meanwhile, James Diggles had been laid to rest at St. Matthew’s and on his grave stone is the following verse from the book of Psalms in the bible:

They gather themselves , together they hide themselves,

They mark my steps when they wait for my soul.

He hath delivered my soul in peace

from the battle that was against me;

For there were many with me.

But thou, o god, shall bring them down

into the pit of destruction:

Bloody and deceitful men shall not live out half their days,

But I will trust in thee o god

Ironically, the words of the epitaph came true as Anthony Bray, the man who was convicted of the manslaughter of James Diggles, died at the age of just 39 in 1843 and was buried at Christ Church, Woodhouse Hill, Fartown.

This brought to the end to an ill-fated event that has disappeared into the mists of Rastrick history. A story of decent people being attacked by oppressive aggressors, resulting in a dreadful conclusion for which the perpetrators went virtually unpunished.

As an aside, poaching was considered a serious offence in Georgian times and it resulted in the introduction of the Game Laws of 1816 where the penalty for poaching or just being in possession of a net during the hours of darkness could result in transportation beyond seas for seven years.

A later Act was the Night Poaching Act of 1828 where, upon 1st conviction, a person can receive three months with hard labour, on 2nd conviction, six months with hard labour and upon 3rd conviction, seven years transportation beyond seas.

The 1828 Act also states that any gamekeeper or servant of land owners, lords of the manor etc, or any person assisting such gamekeeper or servant, to seize and apprehend such offender upon such land, or in case of pursuit being made, in any other place to which he may have escaped therefrom, and to deliver him, as soon as may be, into the custody of a peace officer, in order to his being conveyed before two justices of the peace; and in case such offender shall assault or offer any violence with any gun, crossbow, fire arms, bludgeon, stick, club, or any other offensive weapon whatsoever, towards any person hereby authorized to seize and apprehend him, he shall, whether it be his first, second, or any other offence, be guilty of a misdemeanour and being convicted thereof, shall be liable, at the discretion of the court, to be transported beyond seas for seven years, or to be imprisoned and kept to hard labour in the common gaol or house of correction for any term not exceeding two years.

The Night Poaching Act of 1828 has never been repealed and between the years 2014-16 there were 123 people convicted of offences contrary to it but magistrates are now instructed to fine guilty persons rather than to send them to Van Diemen’s Land ……….. or Tasmania, Australia as we now know it.