FOURTEENTH CENTURY RASTRICK

This project was inspired by the 1314 Manor of Wakefield survey of tenants in Rastrick and Fixby published in J Horsfall Turner’s ‘History of Brighouse, Rastrick and Hipperholme’, supplemented by other manorial court records and the 1379 Poll Tax record for the West Riding of Yorkshire. The Survey was transcribed by John Lister but not published by the Yorkshire Archaeological Society until 1917; however he allowed Turner to use extracts two decades previously. Because the survey deals with different legal obligations and revenue streams, some people are mentioned three or four times.

DOOMSDAY

In 1086, the Doomsday book records one carucate of land at Rastrick and one at Fixby, both wastes. Known in the North as a hide, each unit was the amount of land that could be ploughed by an ox-team, about one hundred and twenty acres, divided into eight oxgangs or bovates, each being fifteen acres or a day’s work.

THE FEUDAL SYSTEM

The King owned everything and everyone else had use of land and buildings at his will, in exchange of goods and services. Great lords like the de Warennes, who held Wakefield manor, were expected to provide men for the King’s armies and employed stewards to manage their estates, often the lords of sub-manors like Henry de la Weld of Toothill and Sir John de Doncastre.

Peasants usually worked a few acres on their own behalf in exchange for providing services and goods to the lord of the manor. Typically, three days’ work a week on the lord’s demesne land, extra at ploughing and harvest, and goods, often a hen at Christmas and eggs at Easter in exchange for the right to a house and for use of land.

THE MANOR OF WAKEFIELD

In a manor with twenty tenants within a few miles, this worked. The Manor of Wakefield covered one hundred and fifty square miles, so even if goods could be transported to Wakefield, dealing with thousands of hens or eggs would be a challenge to any steward and it appears that most obligations in the Rastrick area were commuted to money rents earlier than elsewhere. In the south and east of England, the traditional arrangements for service were still the norm in the early fourteenth century and seem to have been retained in townships close to Wakefield and Sandal.

By about 1220 the Lord of the Manor of Wakefield let half the Fixby township as a sub-manor and later land at Toothill formed another sub-manor. The Manor of South Fixby comprised a carucate of plough land (one hundred and twenty acres), leaving the same amount at Rastrick in the Manor of Wakefield. By the end of the century, Fixby manor was held by the de Totehill family (who also acquired the Toothill manor in 1360). This may have originally been demesne land.

THE LOCAL POPULATION

In 1286 there were only six freemen in Rastrick and a similar number in 1314. Most people were peasants (villeins, natives, bondsmen) who had to live in the manor, as directed by the lord or his steward. They were not free to live where they chose or do as they wished and if they wanted to change anything about their circumstances, that would not be free; they had to pay a fine (or fee) to the lord to get permission.

A freeman could hold native land but an un-free man could not acquire access to free land. So, whilst a free man like John del Okes paid four pence homage and fealty for his toft and fifteen acres of ploughland (a bovate), Matthew de Toothill paid nine shillings and eleven pence for his native ploughland despite its being only three quarters of the area. Consequently, many tenants were indebted to the lord. A toft might be a messuage with rights to common land,or refer to the fact that it was on a hill.

In addition to rental payments, natives and villeins had to:

- Live in the manor and meet any obligations to the lord; at Rastrick most had to help repair the mill dam.

- Maintain the land and houses they occupied as per local laws, and work with and pay their contribution to plough teams used on the land they occupied and contribute to the harvest.

- Grind their corn at the lord’s mill.

- Attend the manorial court as required (a minimum of twice a year) and use the manorial courts to settle any differences and disputes. Boys were often introduced to the court leet from the age of thirteen years.

- Women had to obtain the lord’s permission to marry, and pay a fee, and any unmarried woman bearing a child also had to pay a fine.

They were forbidden to:

- Engage in any trade without a licence (baking, brewing, blacksmithing, tailoring etc)

- Use any resources from the manor other than from the property they held (pasture, green wood, drywood, pannage) without payment or permission.

- Cut wood on the land they held except to maintain or repair the land or house they occupied. They could remove fallen wood from their own and the lord’s land, by hook or by crook.

- Transfer their tenancy or sub-let without the lord’s permission.

LAND AND PROPERTY TRANSFERS

At the end of a tenancy or on the tenant’s death, the land and any buildings reverted to the lord who could re-assign at will. In practice by 1300 the lord would re-assign land to the tenant’s heir in exchange for an entry fee (heriot). The best example to support this comes from Fixby where the de Totehills seized five bovates and six tenements in 1294 and 1297 after Roger de Hoderode died. They were forced by the King to return these to his cousin who was heir in 1321, although “cousin” could refer to a nephew or grandson.

However, certain manorial rights were sold for short periods to tenants, apparently after a bidding process. This included running the mill, stone getting, managing woodland and pannage, which might be let on an annual basis.

NAMING

In 1314, most people only had a fixed Christian name. They might otherwise be identified by their place of abode or birth, their occupation, their parentage or by a nick-name or by-name.

So, John Cissor could also be known in documents as de Hyperom, le Taillour, fil Henry, whilst locally he might be known as “Short” even if he was tall.

In consequence it is not always possible to follow the history of one individual confidently, although it is most likely John Cowerd or Couhird is John le Cowhird de Bradley who paid marriage-right in 1311.

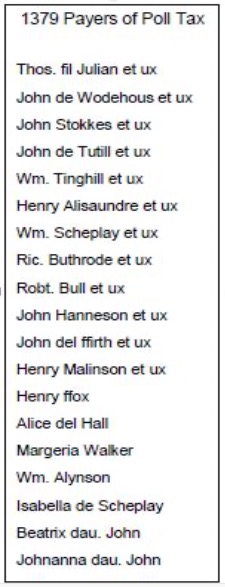

By 1379, many people had heritable surnames; neither of those recorded locally named Taylor nor Smith were tradesmen although most names in Rastrick were patrilineal like Hanneson.

This transition is demonstrated in the manorial records. The constable of Rastrick was called Thomas fil Julian in 1368, Thomas Gillison or Julianson a year later, whilst in 1370 he is referred to as Thos. Julyan, before everyone settled for Thos. Gilleson by 1379, except the enumerator of the Poll Tax!

HOME LIFE

Given what is known about the better medieval buildings in the Calder valley, it is reasonable to assume that dwellings and some outbuildings were largely constructed of timber frames, probably infilled with wattle and daub, mainly single bay, about sixteen feet or 4.8 metres long. They were probably thatched although Adam Batte’s antics suggest that some local buildings were roofed with stone slates (thakestones). Floors were usually beaten earth covered with rushes with a central hearth for heating and cooking, the smoke rising to the rafters, perhaps with loft areas on the sides to store household goods as well as a chest for threshed grain.

Fodder and some animals were housed in smaller buildings and any ovens would probably have been in a separate bakehouse because of the risk of fire. Even if people could not trade in baked goods, a single firing of an oven using bundles of twigs could cook a range of dishes using the same heat once the bread was baked. Many tenements would also have included a small shelter containing a long-drop toilet.

Clothing would have been largely home-spun; few could afford white linen. Women wore a long loose shift underneath a more fitted kirtle, both woollen. Over these women might have worn a surcoat and/or a cloak.

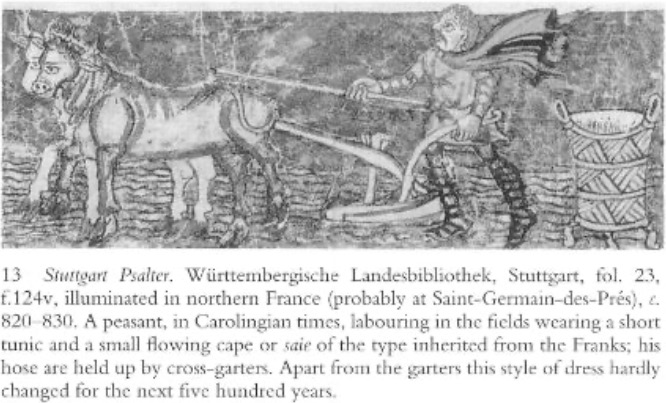

Men wore loose braies or breeches held below the waist by a girdle to which they might also attach woollen hose which would cover their legs below the braies. On the upper body men wore a woollen tunic long enough to cover their braies, sometimes tucked into the braies girdle, later gathered into a belt at waist level.

Both men and women covered their heads, the men with close fitting linen coifs; women’s styles were more varied.

TOWNSHIP GOVERNMENT

Townships were supposed to be self-governing with officials elected from the tenancy within the township. The elected officials had to perform their task and attend the main manorial court at Wakefield every three weeks. The grave or greave organised collective farming activities like ploughing, the constable dealt with law and order whilst the pinder seized stray animals and locked them in the pound. The ale tasters licensed brewers and checked quality.

The basic maintenance of hedges, boundary walls, ditches and roads immediately around their land were the responsibility of the individual tenant, although improvements might be undertaken by one of the six communal work days annually. These were also responsible for maintaining communal structures like wells, the pound and the mill dam.

THE MANORIAL COURT

The elected officials would also present cases to the bi-annual tourn and court leet which dealt with minor transgressions as well as land transfers; the very brief minutes suggest that most cases had been decided locally before the lord’s steward and scribe arrived to record them. The court was held alternately at Brighouse and Rastrick, raising revenue and enforcing political, economic and social norms. Tenants could also raise cases against other tenants, and those outside the manor against the manorial tenants.

Most courts fined a long list of tenants who took dry wood, green wood, pannage or fodder from the lord’s land, or cut trees, fished or traded without a license.

Failing to present a case promptly to the court was a much more serious offence; drawing blood might attract a fine of 20d; covering up a fight could lead to a collective fine of 20s to be paid by the township.

Failure to attend the court also led to a fine, which might be higher if a case against you had to be postponed. Accusers paid a fee to open an inquiry. Often the two sides would then find a resolution and pay a small fee to conclude the case at the next session. If the case went against them, the defendant had to pay recompense, damages and a fine. Anyone repeatedly failing to attend court when summonsed would be arrested and escorted to Wakefield.

EARLY FOURTEENTH CENTURY RASTRICK

The 1314 survey recorded free men who do not appear to have occupied manorial land, free tenants owing only fealty and homage and “nativi”, the native unfree population. It also records who has a tenement, a dwelling with outbuildings, and it appears that some of the nativi did not have dwellings in the township. It is possible that they lived outside the township, or they lodged with family or friends who had dwellings. It might also be that some pasture land was transferred to younger family members and that older members only transferred their ploughland to their heirs as they aged.

There were twenty-four tenements held by manorial tenants in Rastrick and a just over a hide of ploughland (one hundred and twenty acres) as well almost another hide in the remaining half of Fixby.

The ploughland at Rastrick was held by seventeen tenants of whom John del Okes and Thomas de Rodes (from Brighouse) were the only freemen. All those with ploughland occupied tenements except Thomas de Rodes. None held more than fifteen acres of ploughland and most also held pasture land. More pasture was held by sixteen other tenants from Rastrick and other townships.

In Fixby, six free tenants held seven bovates (one hundred and five acres) but only two held any pastureland. Only thirty-eight acres of pasture in total had been carved from the remaining waste in the township. Five of the free tenants paid extra for fires, suggesting that they had chimneys of some sort that were not present in any other houses. It is likely that the smaller tenants on Fixby pasture land primarily lived in and held land from the South Fixby and Toothill sub-manors, the latter held by the de la Weld family.

The total acreage in Rastrick occupied by tenants of the Manor of Wakefield was three hundred and forty acres, or just over half a square mile.

The fact the John de Botherod and John del Okes ploughed their own land and did not pay plough fees as a result suggests that the ploughland was not all contiguous, Boothroyd and Oaks being outside the main arable area.

A list of the tenants and their holdings is here

1314 was probably the time of maximum occupation in fourteenth century Rastrick. The following spring it rained and continued to rain throughout the summer. Corn did not ripen nor forage for the winter. By the time it stopped raining in 1317, the Great Famine had reduced and weakened the population, seed corn had been eaten and livestock killed.

MID-CENTURY RASTRICK

After the Great Famine, it reportedly took five years for agriculture to recover and by then Edward II was engaged in a fight with many of his own lords which culminated in his wife’s deposing him in 1327 and his death. Edward III’s full accession in 1330 heralded a period of costly military activity in Scotland and the continent. It is inconceivable that the De Warennes did not provide the king with men from the Manor of Wakefield for Scottish ventures and some may have gone to the continent.

The manorial records suggest that law and order was breaking down locally long before the Black Death, not least as the king claimed men to fight his wars. The De Warennes’ domestic situation may not have helped either. The 8thearl was born sometime before 1286, when his father died at a tournament. Consequently, John succeeded his grandfather as a minor sometime around 1300. After a first marriage failed to produce an heir, he remarried. As he approached his fifties, the chances of an heir were dwindling and the earldom would be extinguished on his death, and the Manor returned to the king. That uncertainty about who would be running the estate would not encourage those with choices to invest locally and might encourage people to settle matters as soon as possible.

The number of fines recorded for drawing blood was much increased and many incidents involved multiple defendants.

In 1331:

For brewing against the assize constantly, Agnes daughter of Dyote de Lythwayt, and Elena wife of Robert son of Roger, fined 12d each.

That year there were a massive number of fines for transferring property without license throughout the manor.

Another example suggests that even a relatively prosperous freemen was not immune:

Henry de la Weld (probably of the Totehill manor and previously steward) pays a 6d fine to have an inquisition regarding the carrying away of wood from Clay Royd (condoned).

It was found that “Beatrice widow of Thomas del Rode, Matilda del Okes and Matilda daughter of John Couhird carried off wood belonging to Henry de Weld. And that John del Bonderode’s waggon knocked the roof off the said Henry’s grange and that Avota daughter of Richard, Juliana the wife of Richard, and Nicholas Henry’s tenant carried the roof away, Therefore, order is given to attach them for the next court at Wakefield. Also, that Adam Batte carried away forage belonging to Henry from the same grange”.

The published manorial records do not indicate what penalties were imposed but you can’t keep a good man down:

At the tourn in 1332, “Adam Batte for digging thakestone on Rastrick High Road and damaging the road, fined 12d”.

And Henry son of Adam del Broke fined 12d for drawing blood of Roger son of Richard, then:

Richard son of Peter, plaintiff against Henry by ye Brok because his cattle have trampled and depastured Peter’s grass. Henry denies this and an inquisition is called.

Roger son of Richard plaintiff against Henry by ye Brok that a certain time and place Henry beat, assaulted and committed other enormities against him, Henry comes and pleads not guilty and an inquisition is to be held.

At a later court:

Richard son of Peter plaintiff against Henry by ye Brok, compromise on plea of trespass, Henry fined 2d.

Roger son of Richard plaintiff against Henry by ye Brok – compromise on plea of trespass, Henry fined 2d.

And in 1332, Henry de la Weld transferred the Manor of Toothill to William de Riley. He may have held on to some of the land.

In 1339, he disposed large areas in Woodhouse, to his son and possibly a married daughter:

A messuage and fourteen acres at Woodhous were transferred to Robert de Bollyng and Beatrix his wife, and his heirs but if he dies without heirs to revert to Beatrice and her heirs. The fine is only three shillings as the land is barren.

For six shilling and eight pence he transferred twenty-four acres at Woodhus to John son of Henry, and Margaret his wife for the term of their lives, with reversion to Henry and his heirs.

It’s worth noting that in 1362, Adam de Topgreve, Rastrick, paid heriot for a messuage, fifteen acres and one rod, indicating the age of the local location name.

THE BLACK DEATH

Within the context above, the Black Death in 1348 took its toll on an already depleted population.

In 1348, Agnes Benne paid twelve pence heriot for a messuage, and parts of a bovate in Rastrick on her uncle John Steel’s death. The value suggests that this included two or three acres of ploughland. However, John son of Henry de Toothill paid three shillings and four pence for a messuage, bovate (fifteen acres of ploughland) and four acres (of pasture) at Redland in Rastrick, on his father’s death. These were just a couple of the land transfers recorded over the next couple of years.

The detailed land transfers relating to Fixby land held by Margaret de Toothill, wife of William of Thornhill, suggest that male Toothill heirs were not available.

We do not have population figures for the period immediately after the Black Death but in 1349 many tenancies were claimed by nieces and cousins rather than sons and daughters and on occasion the steward actively hunted down successors from the wider family. When there is no successor, the manor can only achieve tenancies at a discount of twenty-five to thirty percent.

THE POLL TAX IN 1379

The poll tax of 1379 indicates the decline in the population; in Rastrick a mere twelve couples and five single people were taxed, single people paying the same fourpence as a couple. Five of the men were called John and three each called Henry and William. Two of the single women were definitely unmarried and probably lived with one the couples, which might also be true of the other single women and the men. At Fixby, there remained one couple and two single women, probably their daughters.

Obviously, the tenancy survey of 1314 and Poll Tax in 1379 are recording different things. The manorial survey only identifies the heads of household owing fealty to the lord of the manor, inevitably missing some free men and those living outside the manor (in Fixby or Toothill for example). The Poll Tax lists everyone in the township over the age of fifteen years. Neither attempts to identify family structures.

However, it is evident that in the preceding sixty years, the population of Rastrick had halved, and not one of the fifteen or so resident households was trading or engaged in mercantile activity. The situation nationally was similar with the decline between 1300 and 1350 only being reversed by the late sixteenth century.

It is not surprising therefore that the petition of 1606 to re-instate the chapel at ease in Rastrick noted that there were only twenty-four households, not dissimilar to the number in 1314.

Sources

The History of Brighouse, Rastrick and Hipperholme, Joseph Horsfall Turner 1898, reprinted … (includes the 1314 survey and 1379 Poll Tax lists).

The Wakefield Court Rolls Series, The Yorkshire Archaeological Society

Volume III 1331-1333 editor Richard Vaughan 1982

Volume II 1348-1350 Second Series Editor Richard Vaughan 1984

Volume VI 1350 1352 editor C.M Fraser 1985

Volume XII 1338- 1340 editor C.M.Fraser 1999

The English Manor c1200-c1500, Mark Bailey 2002

A Dictionary of English Costume 900-1900, CW and P Cunnington 1960

The History of Underclothes, CW and P Cunnington 1951