QUARRYING AT CARR GREEN

When you stand on Toothill Bank and look to the right, there are spectacular views looking across to the hills of Southowram and down towards Brighouse. Between the trees you can make just make out St. Matthew’s Church and looking straight ahead, you see the sheltered housing flats at Chapel Croft. Crowtrees Lane is behind that and then you will see the plentiful rooftops of the many houses at Mayster Road and Field Lane estate.

In the foreground are pleasant green fields that sweep down the banking towards a stream that bubbles out of the ground near to the slopes of Round Hill. The school fields and cemetery at Carr Green are also visible and this pleasant view doesn’t give much indication as to what went on in the area below prior to 1955.

This map shows that there were quarries at Carr Green, known as Southage’s Quarry to many people. They were located between Carr Green Lane to the south and Ogden Lane to the north in the area presently occupied by the Carr Green Junior & Infants School, along with the associated playing fields. The quarries were serviced by a cart-track known as Quarry Road which is shown as starting near to the word TOOTHILL and heading due north towards the bottom of Toothill Bank.

This is a short video of me walking down the old Quarry Road from Carr Green towards Toothill Bank which I have posted on YouTube. It is very overgrown nowadays and a shadow of its former self. In times of very heavy rain, the stream overflows the drain where the water would normally sink underground before emerging again in the small valley that forms the golf course at the Rastrick Golf Club. When the drain cannot cope with all the water from the stream, the excess usually runs down Quarry Road making it very boggy underfoot.

This photo must have been taken just prior to the Southage’s Quarry closing in 1955 as the lighter coloured houses to the left of Sladdin’s Mill chimney is Holly Bank Road on the Field Lane Estate where building commenced around 1952. Just beyond the quarry are the prefabs at Chapel Croft which were erected just after the 2nd WW. Crowtrees Lane is visible just behind them. Between the two close walls in the foreground is Quarry Road. Look closely at the gap in the wall and you will notice a stone gatepost on either side of the wall with an additional gatepost in the centre. You can see the tracks in the soft ground leading from the bottom left of the photo towards the gates. Cart traffic would then head down to the right towards the bottom of Toothill Bank. Now look at the photo below taken in April 2020 and the same three gateposts (highlighted with the white lines) are still there today.

This photo is looking up towards Toothill Bank from Quarry Road, the opposite direction to the black & white picture with the three gateposts highlighted. The direction of the tracks on the black and white picture are also superimposed onto this photo to show the general direction back towards the quarry which is now shrouded by trees.

Another view of the three gateposts that lead from Quarry Road into the field towards the quarries.

The above photograph shows how overgrown Quarry Road is nowadays when travelling from Carr Green

The above photograph shows the old gate posts at the bottom of Carr Green Lane. On the other side of the gates, the track leads towards the quarries and the grass banking leading up to Toothill Lane. The start/end of Quarry Road is just through the gates and off to the left.

Very difficult to see but in the middle of the brambles is the right-angled corner of the wall that came down from Carr Green Lane ( to the left of the photo) whilst straight ahead is the start of Quarry Road heading down towards Toothill Bank where it enters the man road opposite the Rastrick Bowling Club.

Terraced houses were located at the Toothill Bank end of Quarry Road which were demolished around 1969. Many people of a certain age can still recall living there with their families when they were much younger.

Gate to the public footpath from Toothill Bank into the fields leading down to the quarries.

Footpath from Toothill Bank skirting around the top of the hillside quarries.

Old stone fencing post surrounded by broken down dry-stone wall

Moss covered stone remnants from old quarry buildings lie scattered under trees.

The stream that flows through Carr Green springs to the surface at Lower Cote, Fixby. It services the water trough on Clough Lane opposite the Clough House and during times of heavy rain you will often see water emerging through the wall at that location and running down the gutter towards the M62 motorway bridge.

The water sinks back underground at that location and re-emerges in the valley between New Dick and Round Hill near to where the targets were located on the old rifle range at Toothill Bank. It flows as a steam above ground past the bottom of Carr Green Recreation Ground before entering a culvert and continuing underground under Quarry Road before re-emerging once again in the Rastrick Golf Club grounds. From there, it filled the dam at Rosemary Dyeworks, known to many in later years as Walshaw Drakes. It was again culverted under the old quarry at Bramston Street Recreation Ground and eventually re-appears under the railway arches at Bridge End at the rear of the taxi office, where it flows into the River Calder.

Horsfall Turner mentions the stream in his 1878 book, Independency at Rastrick which is a book about the early days of Bridge End Chapel. He describes it as Rastrick Beck, ‘once a beautiful clear stream which discharges its impurities into the River Calder. The inhabitants are ashamed of it and have, for a considerable distance, covered it like a common sewer’. Thankfully, the stream is back to being fresh clear water after over a century of abuse. The above photograph shows the drain where the stream goes underground at Quarry Road.

The stream occasionally overflows and bypasses the culvert. As a result of this, a trench has been dug at the bottom of the field adjacent to the Quarry Road to drain the excess water away, allowing it to soak back under the ground.

This walk was photographed in the Spring of 2020 during the Covid lockdown, when not a great amount of water was flowing down the stream. I returned in February 2021 after some heavy rain and found that the drain couldn’t cope with all the stream water but the overflow trench was working perfectly. At the point where the stream falls into the soak-away ditch, the water sinks underground so quickly that I suspect some old underground quarry workings are taking the water away so quickly. The ditch would just fill with water under normal conditions.

Following the stream along its course, it runs in the valley between new Dick and Carr Green playing fields before entering a boggy area where a variety of march grasses grow in abundance.

As the ground rises up towards the motorway, we come to the place where the stream flows out of the hillside. There are two small water courses that merge below the eastbound carriageway of the M62. The water has reached this location by travelling under the motorway through a culvert after beginning its initial journey at Lower Cote, travelling down to the stone water trough opposite the Clough House Inn / Four Sons before emerging here.

This is the second water course that appears from another culvert situated in a small valley just under the perimeter of Rastrick Cricket Club. The culverts are fed by springs that rise in the fields between the motorway and Fixby Golf course, on the hill leading to Ainley Top.

Another tributary from these fields flows into the land behind the houses on New Hey Road just down from the motorway bridge coming from Ainley Top. This fed ‘Jagger Dam’, the holding area for the former John Smith’s Mill on Dewsbury Road. This stream travels under Dewsbury Road and the former cricket field at Badger Hill behind the Sun Inn. It filled the dam for the former Spout Mills before continuing its journey under Delph Hill and through the small valley between Tofts Grove and Crowtrees Lane. It then filled the dam for Sladdin’s Mill at the bottom of Tofts Grove / Jumble Dyke before travelling under The Orchards and Castlefields Drive. It meets up with the stream from Carr Green underneath the Bramston Street recreation ground, eventually emptying into the Calder at Bridge End.

It is unbelievable how important these streams were as if they dried up, the mill dams could not be filled and the steam powered machinery in the mills would not be able to function. This would throw hundreds of people out of work but there is no record of either of these streams ever failing to provide the necessary amounts of water.

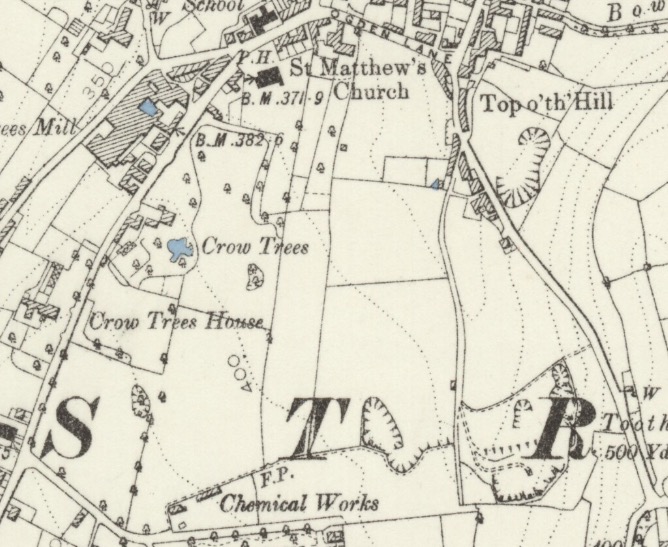

The 1854 map (left) shows that there was a sandstone quarry at Carr Green and we know from old newspaper reports that the hillside at Toothill Bank was being quarried for stone at that time.

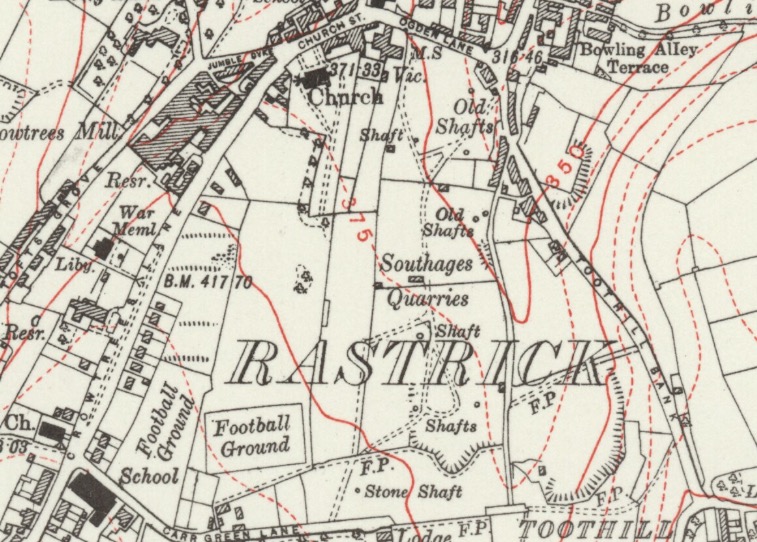

Compare this to the bottom left map from 1894 where there is no mention of quarrying at all though it was still going on. Move on 40 years to the 1934 map on the right and technology had developed to such an extent that shafts could be cut through the stone and the valuable commodity was being hauled to the surface by steam cranes rather than huggers bringing it up via ladders and leather back-packs.

The above maps are reproduced with the permission of the National Library of Scotland

On the 1934 map, there are several shafts that were sunk to replace open cast mining. Many of these were over 100 ft (30 metres) deep and this allowed the delvers to get down to where the good quality stone was located.

The area became known as Southages Quarries with a few different independent quarry owners such as the Bradbury’s but the main one was Bentley & Smith. They had quarried at the Lillands and Castlefields areas of Rastrick since 1881 and employed 179 men at Crowtrees / Carr Green at the height of their operations between the 1st & 2nd World Wars. There was a massive decline in the stone industry following the 2nd World War and Southages was the only quarry to re-open after hostilities ceased in 1945, continuing for another ten years before finally closing for good.

Brick had become the main material for building by this time and most of the new local authority housing developments that commenced after the war saw houses being built of brick. That product was also plentiful in the area with brickworks under the cliffs at Rastrick Common and a huge manufacturing plant in the bottom of Lower Edge.

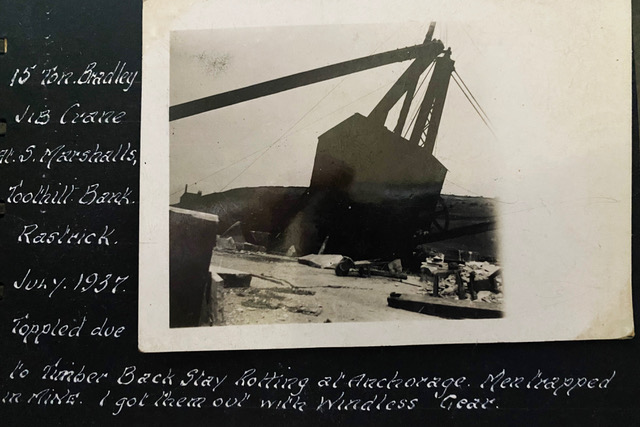

A stiff-leg derrick crane at Carr Green which was used to haul large blocks of stone from the bottom of the shafts. This crane consisted of an upright mast with a boom or jib from which the steel cable was lowered or raised from the shaft by means of the winding gear which was powered by a steam engine, housed in what looked like a large garden shed. Two ‘stiff legs’ or ‘back-stays’ were made from timber and were secured to the top of the mast whilst the base of each leg was fastened to a huge stone block. These blocks were then surrounded by other large stones to increase the weight and give additional stability to the whole structure. It was designed to stop the crane from tipping over when lifting heavy loads.

As you can see from the photograph below, this didn’t always go to plan and on this occasion the crane toppled forwards due to the weight of the lift and the failure of one the stiff-legs. One of the legs smashed through the roof of the engine house and no doubt, work was delayed for a few days until the crane could be secured back into position.

In the background you can clearly see the ridge line at the top of the banking, a path know to many locals as New Dick.

William Walter Sykes was a crane inspector for the British Engine Insurance Company. He was connected with New Road Sunday School at Rastrick and a friend of my grandfather, Arnold Bottomley. William kept a journal of the many inspections and incidents he attended throughout the country on behalf of his employers. This journal entry was sent to me by his grandson, Nicholas Sykes and shows that William was sent to this particular accident.

Along with a similar photograph of the accident but taken from a different angle to the one above, William wrote in his accompanying notes, ’15 ton Bradley Crane at S. Marshalls, Toothill Bank, Rastrick, July 1937. Toppled due to timber back stay rotting at anchorage. Men trapped in mine. I got them out with windlass gear.’ So thanks to his records, we are able to put a background story to what would otherwise be just a photograph of a crane that had toppled over.

The windlass was originally a hand wound mechanism that performed the tasks of getting miners up and down the shafts and they were also used for hauling stone blocks up to the surface. It appears that William hauled the face working miners back to the surface by these means. All the quarries had one available for use in such emergencies.

Having asked around as to what the men were doing in this photograph, Michael Buckley responded by saying that he thinks the men are hammering out a tune on the huge crowbar. Jokingly, he says that they had a band called The Quarrymen (which was the early name for The Beatles).

You can see some of the crane machinery through the door of the engine house.

The photograph below was taken at the bottom of a shaft at Carr Green as the men attached chains to a large stone block in readiness for it being raised to the surface.

Miners being hauled to the surface of the shaft at Southages Quarry, Rastrick. Brenda O’Brien has identified the man in the centre as Patrick Feeney, her husbands grandfather. Patrick’s brother, Michael Feeney is to his right at the top of the photograph.

Above is Mr. Bentley of Bentley & Smith, Southages Quarry, Rastrick. Even the boss gets dirty but still wears a shirt and tie whilst underground.

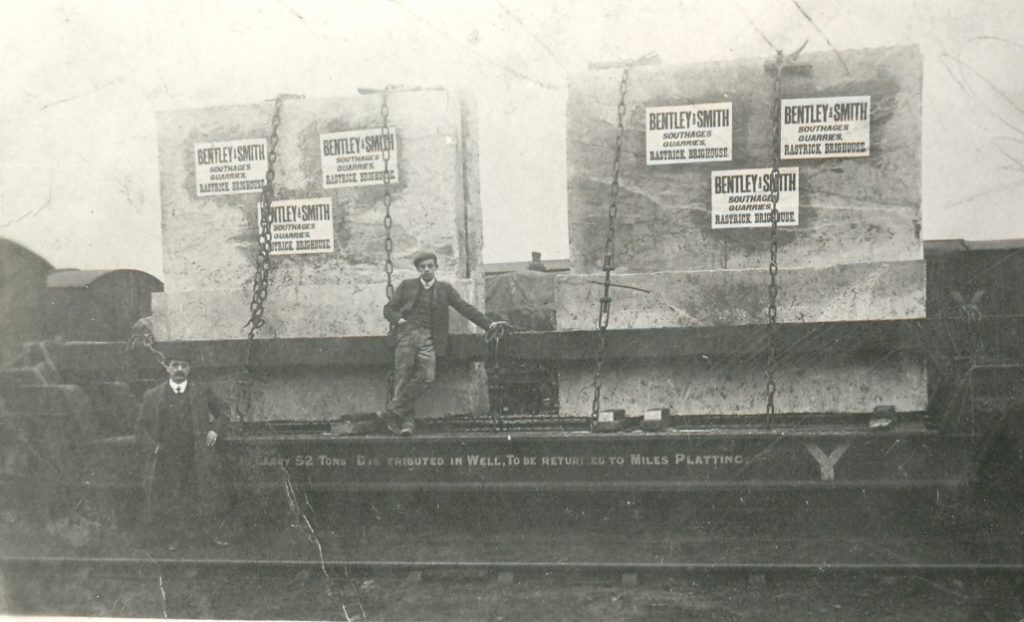

The photograph below has two large stone blocks on a flatbed railway trailer capable of transporting 52 tons.

If you search through the trees, brambles and ivy, you will find some of the huge stone blocks that were used to support the derrick cranes. It is very valuable stone but much too heavy to take home in the boot of your car.

The large flat stone in the bottom photo appears to have been drilled for a securing bolt to be inserted into the centre but the stone has then split. Was this as a result of an accident similar to the one in the old photo, where the crane has toppled over?

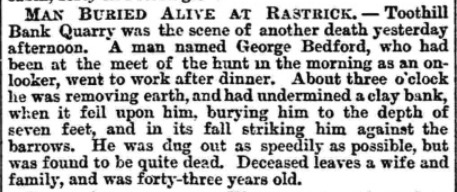

THE SAD STORY ABOUT THE DEATH OF A QUARRY WORKER

Countless men and boys have been killed or seriously injured whilst working in the quarries and delph pits around the Rastrick area. It was a hard and dangerous life with a life expectancy of just over 40 years of age. I would like to tell you about one of these men and his tragic family.

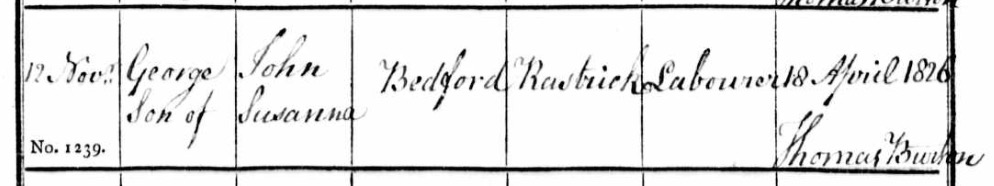

George Bedford was born in Rastrick on the 18th April 1826. He was the son of a quarry labourer, John Bedford and his wife Susannah and was baptised at St. Matthew’s Church, Rastrick on the 12th November 1826. Like his father, George went to work in the local stone quarrying industry as a boy labourer. In 1841, he was living with his parents and four siblings at Little Woodhouse, Rastrick which was the name for area we now call Oaklands. It was close to the quarries at Lillands and was an easy walk for the quarrymen to get to work.

On the 7th October 1849, George married a local girl, Catharine Wrigley. She had come to live in Rastrick with her family from Leinster, Ireland in order to escape the mass starvation caused by the potato famine in that country which killed over one million people between 1845 and 1850. The couple married at St. Mary’s Parish Church, Elland and they went on to have twelve children.

In 1851 the couple lived at Bridge Street, Brighouse, just over the river bridge from Rastrick but they had moved back to Little Woodhouse by 1861 where they lived for the remainder of their lives. George had several jobs in the quarries, either labouring or delving but by 1871, he had obtained employment as a barer in a hillside quarry at Toothill Bank. This involved manually digging through the grass, weeds, stones and soil until he reached the natural stone bed, which could be several feet beneath the surface. Once he had cleared away all the spoil in heavy wooden wheelbarrows and exposed the stone, the delvers would set about extracting the precious commodity. It was hard, back-breaking work and entailed working in the open air throughout the year, enduring whatever weather the elements threw at him.

Life was tough and in the ten years between 1861 and 1871, George and Catharine saw seven of their twelve children die in infancy. The youngest being just seventeen days old and the eldest only two and half years of age. This is something that would be very hard to imagine nowadays.

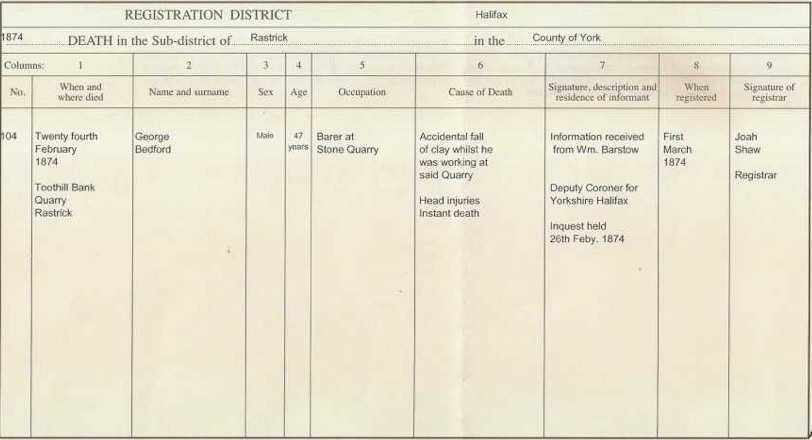

On Tuesday, 24th February 1874, George spent the morning watching the local hunt before going to work after his dinner. At around 3pm, he was with other barers, digging into the hillside, when the clay banking above him gave way. The force threw him headlong against the wheelbarrows and buried him under about seven feet of spoil and rubble. By the time his colleagues had dug him out, George was dead.

He was buried at St. Matthew’s Church in the same grave (plot J37) as his infant children. One of his five surviving children was married whilst the other four were still at home with Catharine.

By 1891, two more of Catharine’s children had died and the other three had married. It was at this sad point in her life that she was committed to the Halifax Union Workhouse as a pauper inmate. In 1892, unsurprisingly, Catharine was showing signs of mental illness and was committed to the West Riding Pauper Lunatic Asylum at Stanley, Wakefield, later to become Stanley Royd Hospital. She died there on the 4th May 1893 and was laid to rest along with her husband George and seven of their children at St. Matthew’s, Rastrick. There isn’t a gravestone to mark the plot.

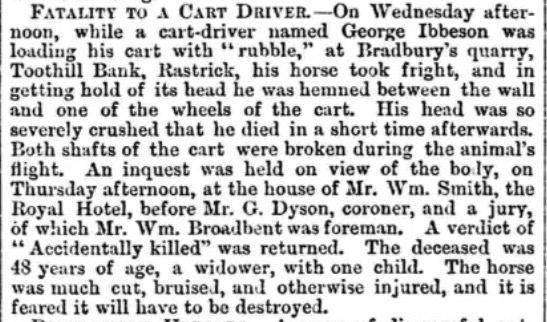

Incidents such as befell the unfortunate George Bedford were not uncommon and an earlier accident was reported in the Huddersfield Chronicle dated 3rd July 1869. In this tragic tale, George Ibbeson was working at Bradbury’s quarry on Toothill Bank when he was trapped between the wall and his horse and cart. His head was severely crushed and he died soon after the accident. The reporter seems to accept the death of the quarry worker but is fearful that the injured horse may have to be destroyed. Such was the value of a human life in those bygone days.