A DOUBLE CHILD MURDER

A sad story about the murder of two innocent children in 1864 at Stackgarth, Ogden Lane, Rastrick that made national headlines.

The main characters in this story are:-

Mary Ann Thompson, d. of Archibald and Mary Thompson of Ballymote, Sligo, Ireland

and

William Dyson, son of William and Sarah Dyson of Rastrick

William worked in the building and construction industry as did several cousins and other family members.

His father took the family to Derbyshire in late 1840’s but William didn’t really settle and following the death of his mother, he joined the army in late 1850s. He was posted to Ireland where he lodged with a local family, Archibald and Mary Thompson in Ballymote, Sligo. Archibald was a local police officer in the town and he and Mary had several children. After a short period of time, William fell in love with one of daughters, Mary Ann and they were soon married at Emlaghfad Parish Church in Ballymote in June 1860.

William decided to leave the army and attempted to set up a business in the construction industry in Ireland but he was unsuccessful and his business failed.

The couple were blessed with a daughter who they named Mary, after the Childs grandmother. Mary was born in 1861 and by June 1863 Mary Ann found that she was pregnant with a second child. William was struggling financially to keep his head above water and made the decision to return to Rastrick and to seek employment there. This meant that he would have to leave his pregnant wife and his baby daughter in Ireland until he found employment and somewhere for his family to live.

On arrival back in Rastrick, William lodged with John Aspinall and his wife at Bridge End. He found employment in the building trade, working for his cousin James Dyson, who was operating as a stone mason and contractor.

James had built several houses in the Rastrick area including some at Stackgarth off Ogden Lane.

Once settled, William brought the pregnant Mary Ann and their daughter Mary to Rastrick where they resided with the Aspinall’s until after their 2nd child, a son, was born on the 2nd December 1863. He was named Archibald after Mary Ann’s father. The fact that both children were called after Mary Ann’s parents proves that she was very close to her own family, a point which is proved later in this story.

Residing in lodgings was not ideal for a young married couple with two small children but cousin James came to the rescue and offered William and Mary Ann the opportunity to rent one of the houses he had built at Stackgarth. Despite having little money and no real furniture to call their own, they decided to take the plunge and move into their new house.

The couples finances were not helped as William spent a large percentage of his wages on drink and socialising with other women in the local bars of Rastrick. In addition, there was a lack of regular income in the building trade during the winter, especially if the weather was particularly bad. There wasn’t any government support or benefit system in those days and so with little money and scant furniture in their home, the situation played upon Mary Ann’s mind. Living in virtually a foreign land and unable to provide the necessities for her two infants whilst her husband was out drinking every night, was not what she had envisaged when coming to live in England. Mary Ann soon became unhappy and depressed.

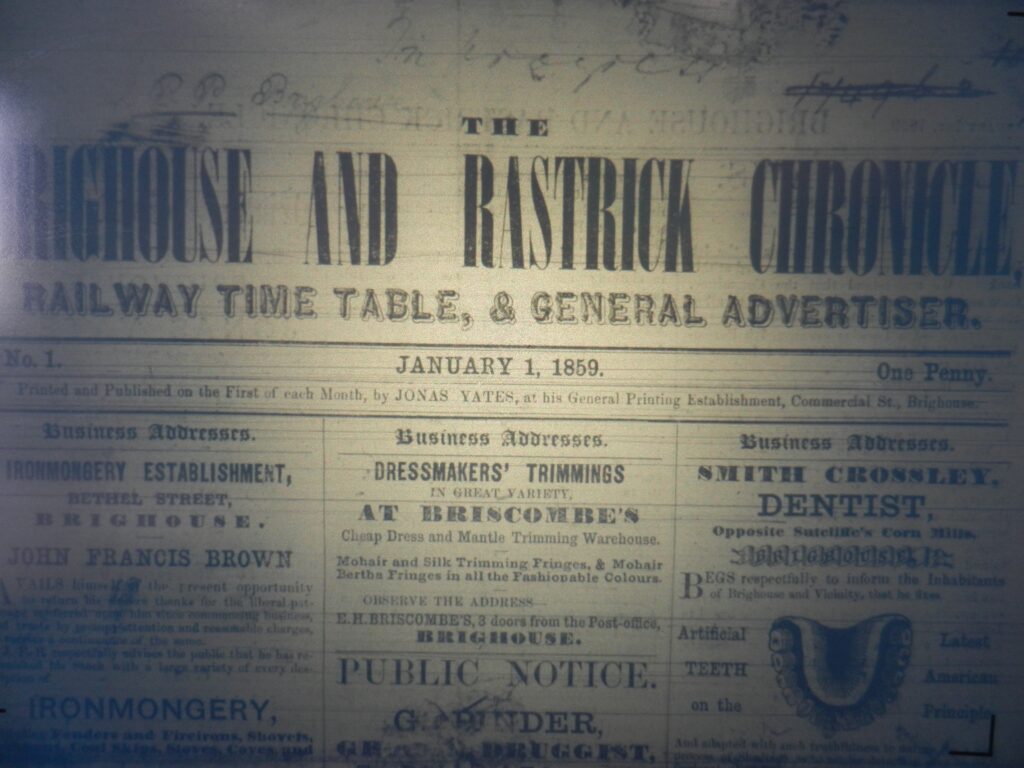

Let us look at newspapers of the time for a moment. The Brighouse & Rastrick Chronicle, Railway Timetable and General Advertiser was the first newspaper in the Brighouse and Rastrick area. It first appeared on the 1st January 1859 and consisted mainly of adverts but it tried to provide the reader with interesting articles about local and national news.

The newspaper was generally boring but occasional newsworthy stories, usually regarding the latest guest speaker at the Brighouse Mechanics Institute or the local Temperance Society. Other equally interesting subjects discussed the amount of money taken in the collection at the Bridge End chapel anniversary service. This was about as good as the reader could have hoped for in Rastrick, therefore, what happened on the 14th April 1864 was a newspaper reporters dream in the quiet village of Rastrick, a place that wasn’t synonymous with headline news stories.

The shockwaves literally reverberated around the British Isles where the story was repeated in almost every newspaper of the time. Word quickly spread around Rastrick of a murder having been perpetrated in the foulest of circumstances. But this was not just a single murder, but involved two victims and the victims were two innocent children. If that wasn’t powerful enough, the murderer was none other than the mother of the victims. It was gripping stuff indeed. As word spread regarding the full horror, many residents of the village were reported to have fled in terror, though they obviously did not know what they were fleeing from. Others, estimated to be several hundred, rushed to the scene to feed their ghoulish yearnings as a full blown Victorian drama unfolded before their very eyes.

Imagine the local ladies of the day, in their large crinoline dresses, wearing large hats or bonnets, or the poorer classes wrapped in shawls, all hurrying from their homes down to the scene, as the news spread. The location of the murders was Stackgarth off Ogden Lane at the home of William and Mary Ann Dyson. What exactly had occurred and how had their young children met their untimely ends?

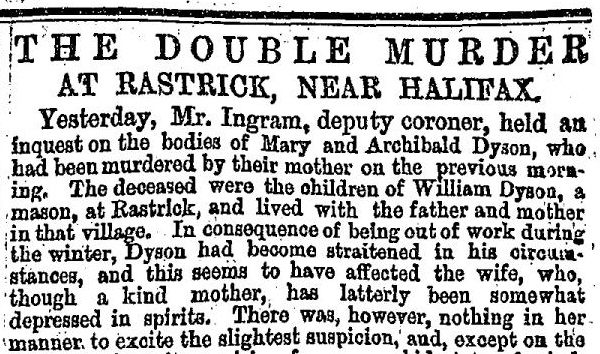

The first locally published reports were conveyed in the Huddersfield Chronicle and the Leeds Mercury and the following month (it was a monthly paper), the Brighouse & Rastrick Chronicle also carried the full story. The content of each report was similar but there were some interesting additions and omissions by some of the newspapers and in true journalistic style, there were many errors. Just how and where the newspaper reporters managed to obtain the finer detail is amazing. They must have been given access to speak with both the murderer and the father of the victims, despite them being in utter shock following the tragedy.

Looking at the Huddersfield Chronicle, published two days after the event, it was reported that the Coroner’s inquest was carried out on the day after the murders. The newspaper account included details of that event also and stated, ‘the usually quiet village of Rastrick was on Thursday morning last, the scene of a horrible murder, which has created the greatest imaginable excitement. The story continued by telling how William went off to work whilst Mary Ann went about her household duties. She then kneaded some flour in readiness for baking and got her starched linen ready for ironing. At 8-15am she was seen coming from the mangle house at the Top of Town, where she had left her washed clothes because it was too early to mangle them.

Mary Ann returned home and nothing more was seen of her until shortly after nine o’clock when she asked a young girl where the policeman lived because she had just killed her two children. The girl ran home and told her parents and the situation escalated from there.

Mary Ann went to the house of Police Constable Bracewell and told him what she had done. William Dyson was brought home from his work and upon seeing him, Mary Ann said, “Oh! William, I’ve killed your two children; could you have thought it of me?” The report says, ‘The poor bereaved man could not utter a word, but reeled like a drunken man and would have fallen but for the kindly help of some bystanders. The wretched woman was then taken by the policeman and lodged in the county lock-up at Halifax.”

The newspaper reported that ‘scores of people surrounded the scene of the murder, wishful to obtain a glimpse of the murdered innocents, who, we are told, will both be interred in one coffin’. It added, ‘The husband is in a most distressed condition at this sudden and tragic end to all his domestic happiness’.

The inquest was held on the following day at the Thornhill Arms (the former Cottage Care Home at the Top of Town). It took four and a half hours for all the facts to be relayed to the jury who eventually gave a verdict of “wilful murder”.

It must be remembered that such a verdict at an inquest did not mean that the defendant was guilty of the offence, it only meant that there was sufficient evidence for a trial to proceed at a later stage.

The Leeds Mercury dated Saturday 16th April 1864 also reported on the murders and whilst very similar to the Huddersfield Chronicle, it included several more witness account details from the inquest.

First to give evidence was William Dyson who gave details about his marriage and said that his wife was an affectionate mother but he had noticed changes in her conduct which led him to suppose she was not all right in her mind.

Mr. Henry Pritchett, surgeon (he lived at The Poplars on Rastrick Common near to the entrance to Bowling Alley), said – On Thursday morning, about twenty-five to eleven, I went to Dyson’s house. I found the deceased laid side by side; the throats of both of them were deeply cut across, as if with a razor or other sharp instrument. Death would almost immediately follow. I saw the mother and asked her why she had done it? she replied, “I’ve done it and what’s done can’t be undone.”. She was very dejected and restless, sighing and wringing her hands.

Wm. Ambler, grocer, (he lived at the Bottom of Town where the grass banking now is, opposite the former Junction pub) – In consequence of what I had heard, I went up to Dyson’s house. The door was open and no-one was within. I went in and found the bodies of the two children laid upon the kitchen floor, opposite the fire, one on each side of the table. There was a good deal of blood on the floor. Five or six inches behind the youngest child there was an open razor (produced in court as evidence), with blood on the blade. The eldest child had a piece of bread in his hand when I lifted it up.

Police-constable Bracewell, West Riding constabulary stationed in Rastrick – My house is about fifty yards* from Dyson’s and at about twenty minutes past nine, the prisoner came to my house and said, “I’ve killed my two poor children, take me and lock me up”. I went to the house and found her statement true. She has since acknowledged more than once that she had taken the lives of her children. When I was taking her to Halifax she said, “I’ve tried to be like others but cannot.” I thought she referred to the condition of her house as there was very little furniture in Dyson’s house.

*The serving constable of Rastrick lived at the house of 13, Stackgarth for over forty years but until the mid-1870’s, he lodged with a family on Ogden Lane that later became Parrat’s shop.

Lydia Aspinall, wife of John Aspinall of Bridge-end, at whose house Dyson had lodged proved that the prisoner lived with her husband on affectionate terms. She was remarkably fond of her children, and always heard the eldest say her prayers. It did strike Mrs Aspinall that before the Dyson’s left, Mary Ann was at times, not right in her mind as she often spoke about dreams and was always imagining some misfortune would occur. Mrs Aspinall said that this had only happened since the last child was born.

The Coroner asked Mary Ann if she had anything to say. She replied, “All that has been said is true”. He then told the jury that it was not their province to inquire into the state of the prisoner’s mind – that was matter for inquiry elsewhere. The question for them to consider was, how these children came to their death and they could have no difficulty in arriving at their verdict as the prisoner admitted that she murdered these poor children. The jury then returned a verdict of “wilful murder”. At the conclusion of the enquiry, Mary Ann was taken back to Halifax where she was later put before the West Riding magistrates, and formally committed for trial on a charge of murder.

At the end of April, the Brighouse & Rastrick Chronicle gave a full report upon the murder, inquest, funeral service as well as the transportation of Mary Ann Dyson to York Castle, to await trial. They even had details of a letter written to her husband from the confines of her cell in the Castle. The report was once again, typically Victorian high-drama and said, ‘one of the most shocking acts of murder ever committed in this district, was perpetrated on Thursday morning, the 14th. The intelligence that a woman had murdered her two children spread with great rapidity through the village and people ran terrified from all directions to the place indicated, and learned that the dreadful news was true, for in the house occupied by William Dyson, a mason, situate at Stackgarth, two fine children lay corpses, weltering in their own blood, the victims of their mother’s cruel hand’.

There were further accounts of the scene saying that ‘The spectacle which met Mr. Ambler’s gaze was truly appalling as the eldest child, Mary, was laid on the floor, saturated in blood still oozing from a frightful gash in her throat and the little child was holding still holding a piece of bread in her hand. A few feet further away was that of the infant, a most beautiful little boy, five months old. His head almost severed from the body, and covered with blood. By the side of its head lay the instrument with which the murder was committed – a sharp razor.’

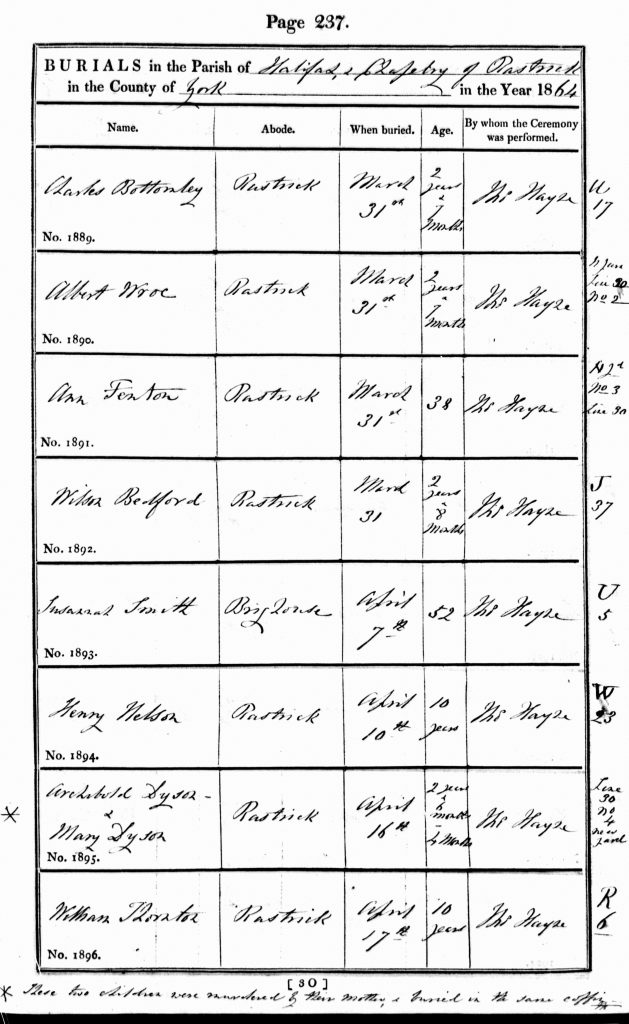

The funeral took place on the Saturday morning, the 16th April at St. Matthew’s church. To avoid overcrowding it was agreed that it should begin at an early hour. At eight o’clock the church bell began to toll. Almost the whole village assembled around the house and in the lane leading up to the church-yard as the coffin was processed to the burial site at the rear of the church.

The burial register entry from St. Matthew’s Church, shows the two children were buried together in the same coffin in Line 30, Plot 4 in the New Yard. Such was the utter disbelief at the circumstances of the deaths that even the burial register was endorsed with the fact that the children had been murdered by their mother, which is most unusual. It read, ‘these two children were murdered by their mother & buried in the same coffin’

There was talk of raising subscriptions for a monument to the two children but the place where they lay is just grass, with a blackberry trying to establish itself.

Soon after the funeral, Mary Ann was committed to York Castle by the magistrates at Halifax to await her trial. She was taken on the train by PC Bracewell from Halifax. When the train arrived at Brighouse station, where they had to change, a large number of people had assembled to get a glimpse of Mary Ann. Astonishingly, she was accompanied not only by PC Bracewell but by her husband also. At Brighouse, PC Bracewell told William Dyson that he couldn’t travel any further with them but William pleaded with the officer who then allowed him to travel as far as Mirfield where they eventually parted. The newspaper told how Mary Ann ‘was convulsed with grief and clasped her husband in her arms’ but at this point, a very strange thing happened. William tore himself away from Mary’s grasp and took the wedding-ring from her finger. Was this some indication that as far as he was concerned, the marriage was effectively over?

Later that week, Mary Ann wrote to William and in her letter it appeared that she had convinced herself that she was about to hang for her crimes. She talks about meeting with the Chaplain who had told about the mercy of God and she said this was a great comfort to her. She added that ‘the Almighty invites the weary and heavy laden and he will give them rest. I felt crushed under a load of guilt. I and another prisoner bowed before Him who is mighty to save; and, glory be to God, I rose with that heavy burden removed; and, dear husband, I feel fully resigned to the will of God, whether I live or die. I feel ready at any moment to resign this fleeting breath, and meet Him, the Judge of the World, knowing that He has cast my sins away from me, as a stone, to the bottom of the sea.’ She ends the letter with, ‘I am, dear husband, your affectionate wife until death – MARY ANN DYSON, York Castle.’

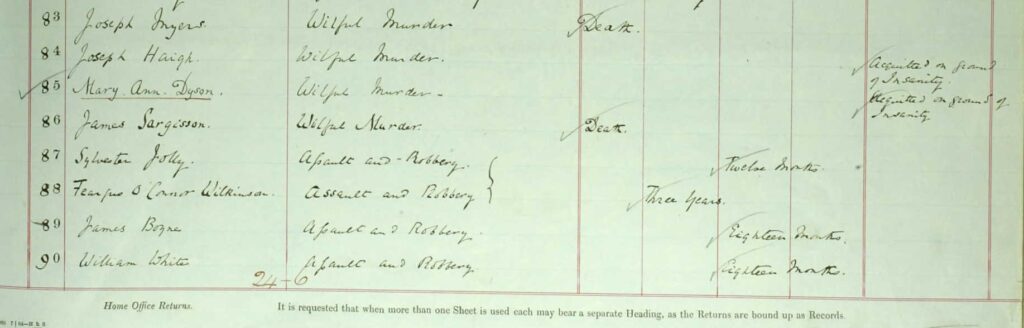

The Assizes at Leeds, where the most serious cases were heard, only sat four times a year so Mary had to wait almost two months before her appointed hearing date. On the 8th August 1864, Mr. Justice Keating took his seat in the Crown Court and told the members of the Grand Jury about the 120 cases they were about to hear. He added that the most serious cases were the four which involve the charge of wilful murder, and the ‘first one that occurs is one of a very melancholy description indeed; it is that of a mother, Mary Ann Dyson murdering two of her children at Rastrick, near Halifax. That the offence of murder was committed in each of these cases there is no doubt. The mode in which it was done, and the circumstances under which it was perpetrated, do rather suggest that the mind of the mother must have been seriously disturbed at the time – whether amounting to a state of mind which will free her from criminal responsibility or not will be a matter better investigated in open court in the presence of a petty jury.’ The judge made was quite clear that her life was most certainly in the balance. The prosecution lawyer was to be Mr. Middleton, and the defence lawyer, Mr. V. Blackburn.

At seven o’clock in the morning of Tuesday, 16th August 1864, the approaches to the Leeds Assizes ‘were thronged with persons anxious to gain admittance, and at nine o’clock, when his Lordship took his seat on the bench, the court was crowded in every part.’ The first case to be heard was that of Joseph Myers, a knife-grinder of Sheffield, who was charged with the wilful murder of his wife. At conclusion of the evidence , his Lordship summed up and informed the jury that the prisoner caused the death of his wife by inflicting knife wounds. There was no evidence of provocation to reduce the charge to manslaughter and he he then asked the jury to consider their verdict. The jury consulted for just three minutes and found Myers guilty of murder.

His LORDSHIP said, “Joseph Myers, you have been convicted of the crime of wilful murder, aggravated in your case by the circumstance that the person you murdered was your own wife, she whom you had promised to love and cherish. I do not desire at all to aggravate the horror of your present position but I would earnestly entreat you to think of that position, to prepare yourself to die, and to look for and endeavour to find that mercy hereafter which you cannot hope for here. The duty remains for me to pronounce upon you the sentence of the law, and that sentence is that you be taken from the place where you are now, to the place from whence you came, and thence to a place of public execution, that you shall be hanged by the neck till you are dead, that your body be buried within the precincts of the prison where you shall last be confined, and the Lord have mercy upon your soul.” The prisoner was then removed from the court.

The second case was that of Joseph Haigh who was indicted for wilful murder at Huddersfield. Following the evidence, the jury returned a verdict of not guilty on the ground of insanity at which His Lordship ordered him to be detained during Her Majesty’s pleasure.

The time had come for the case against Mary Ann Dyson to be heard. Her only hope was to also be found not guilty on the ground of insanity. The same witnesses who had given evidence at the inquest in Rastrick were called upon and the same details were once again heard.

Dr. Henry Pritchett, the Rastrick surgeon, told the court that he was of opinion that at the time when she committed the act she was not sane. He believed she was suffering from impulsive insanity at which Mr. BLACKBURN for the defence, asked the jury whether they could believe “that an affectionate and loving mother, as the prisoner had been proved to be, would, in her sane moments, have committed the crime of taking away the lives of her two children, of her little darlings, as she called them”.

It is interesting to note at this point that the term Impulsive Insanity is not a recognised term in modern times and was only used as a last resort, when all other lines of defence had failed. Even then, there was scepticism as to its validity therefore the defence are really scraping the bottom of the barrel in their efforts to prove that Mary Ann was not sane and thus save her from the gallows.

He told the jury about how Mary Ann was subject to fits when she was younger and how on one occasion, she had thrown herself into the Shannon river. She was eccentric in her manner for some time and on another occasion she ran away from home without her clothes and was not found until the day after. There had been other symptoms of insanity in the family as her brothers and sisters had suffered from disease of the brain, four of them dying from it.

Mr. Pritchett was re-called and he said that the four siblings of the prisoner had died from water on the brain which showed a tendency of a diseased brain within the family and he was still of opinion that the prisoner suffered from impulsive insanity. However, the important issue was for the prosecution to prove that Mary Ann knew the difference between right and wrong at the time of the commission of the offence and the Judge asked Mr. Pritchett many questions to try to establish these facts. Mr. Pritchett insisted that the disease created an impulsion to do the act which she couldn’t control but the prosecution lawyer, Mr. MIDDLETON argued that there was nothing in her conduct which justified a conclusion of insanity. The evidence given only amounted to acts of eccentricity or waywardness.

His LORDSHIP summed up by telling the jury that illness of the mind was the most mysterious of afflictions and he could only put the question to the jury in the way it was sanctioned by the law, that being, whether at the time the prisoner committed this act she knew the difference between right and wrong? If they were satisfied of that, at the time, she did, they would find the prisoner guilty of wilful murder, if they believed that she was not able to distinguish between right and wrong at the time of the commission of the offence, it would be their duty to say she was not guilty on the ground of insanity.

The jury retired for twenty minutes before returning their verdict of NOT GUILTY OF WILFUL MURDER ON THE GROUND OF INSANITY. Mary Ann was ordered to be detained at Her Majesty’s Pleasure. This meant that it would have to be later proved that she had regained her sanity before she could ever be released from prison.

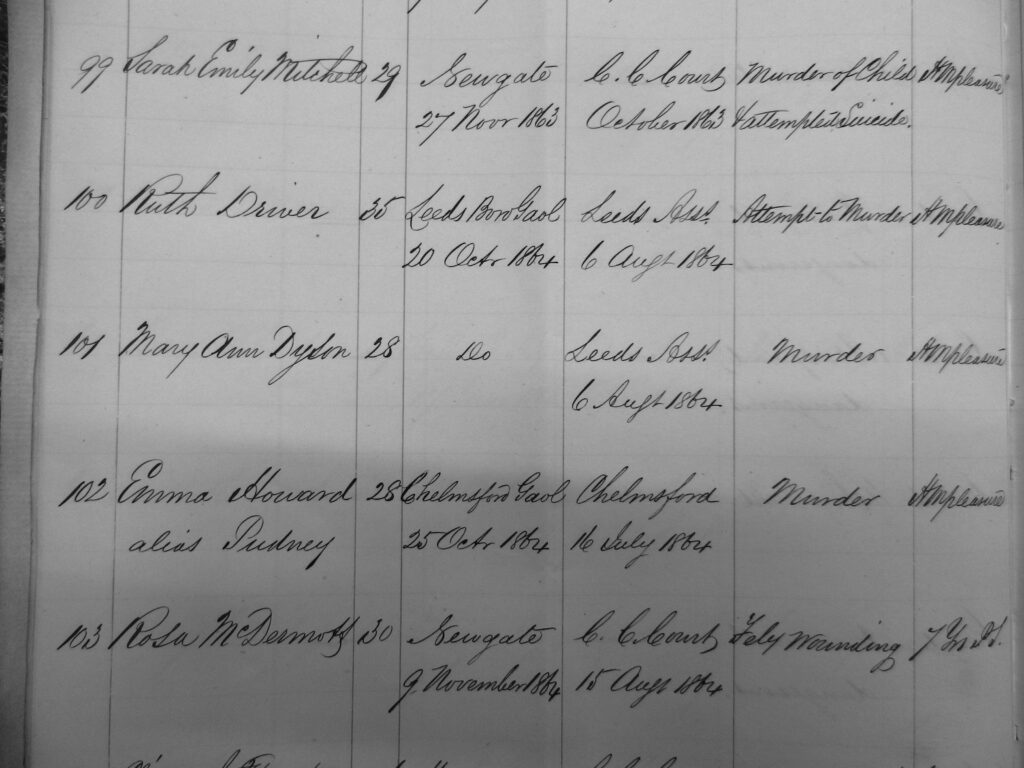

The criminal register from Leeds Assizes (below) shows the verdict of Death in there Joseph Myers case and that Mary Ann Dyson was acquitted on the ground of insanity whereupon she was sent to the Broadmoor Criminal Lunatic Asylum, which had only opened during the previous year of 1863.

To find out what happened next, I visited the Public Records Office at Kew but only found the quarterly returns and the books failed to answer questions regarding any mental health assessments, treatment, visits from husband or family, was she ever released and if so, where did she go ?

The visit was a waste of time and money except for being told that there are more Broadmoor Lunatic Asylum records stored in the Reading Archives, Berkshire, so that would be my next port of call.

After booking out the relevant box online, relating to Mary Ann Dyson’s incarceration, I visited London again and from there, caught a train to Reading. This was a much more fruitful journey and answered some of the questions I had posed.

In one of the first assessments of Mary Ann upon entering Broadmoor, she was described as quiet, well-behaved and in good health. The notes mention that in November 1864, William Dyson wrote to the hospital saying that he thought Mary Ann was quite sane whereupon it was explained to him that the doctors at Broadmoor believed that Mary Ann was definitely insane and was probably insane at the time of their marriage.

In another assessment interview with doctors, Mary Ann described how she had always worried that some harm was going to come to her husband and that she would be left penniless to look after her children. There was a genuine fear of the workhouse in those days which was the place to where families who were incapable of supporting themselves were sent. Mary Ann added that for two weeks previous to the murder of her children, she had slept very little and was very low spirited. She described to the doctors that the thought of destroying her children came to her suddenly and she thought that she must have been out of her mind to even think such things.

In 1870, Mary Ann told the Broadmoor staff in another interview that she believed her husband was not living a reputable life. This was based upon letters from her father as she had not heard from William Dyson for five years. So here we have evidence that William Dyson hadn’t ever been to see Mary Ann whilst she was incarcerated at Broadmoor.

It was at that time that Mary Ann was described as an industrious patient and she was working in the hospital laundry room whilst in the following year, she was working on needlework.

There are several documents in the files which include a reply to an application for Mary Ann’s release in 1868, though who actually made the request is not clear but I rather suspect that it was her father. The request was turned down by the Home Secretary Mr. Gathorne Hardy. A question then for all you Brighouse locals. Have you ever wondered where the names for Gathorne Street and Hardy Street on Bradford Road opposite the Police Station came from? Well it was because of Gathorne Hardy but that is another story for another day!

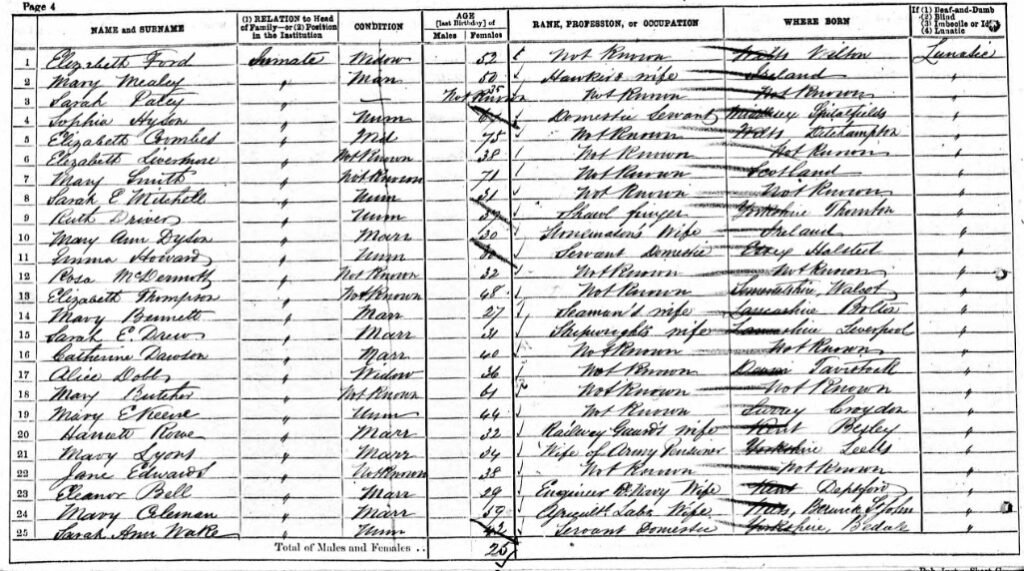

In the 1871 census (below), everyone in Broadmoor was included in the census records, both staff and patients. Mary Ann was no exception. She is recorded in the 1871 census (no. 10) at Broadmoor as a LUNATIC but upon close inspection, every patient was described in this way. Mary Ann is shown as being aged 30 years, married, a stonemasons wife from Ireland.

Suddenly, without warning, William wrote to his wife on the 3rdNovember 1871. This was his first letter he had written to Mary Ann for six years, the year after she was committed to Broadmoor. He reveals in his letter, ‘I suppose you heard of me going to America. I have been and come back again. I am coming to London very shortly and should like to come and see you but I suppose you will not like a visit from me. If you answer this letter, please send it to your father for me.’

Mary Ann must have responded to his letter as William wrote again on the 22nd November and said, ‘Dear Wife, I was very glad to receive a letter from you, I thought you would not send one to me.’ He then talks again about his future visit to London but doesn’t know the exact date but he also informs Mary Ann that he would like to return to America one day. I suspect that he never had any intention of ever visiting her and was happily leading another life, as we will see shortly.

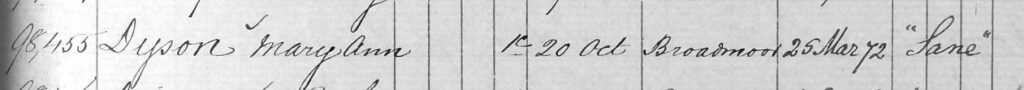

By the following month, December 1871, Mary Ann had another assessment at Broadmoor where, out of the blue, she was declared ‘sane’ on the quarterly return of the Broadmoor Asylum. Around the same time, she received a letter from her parents and from the content, it is obvious that there had been several previous letters, although there is no record of them in the archives.

Any previous thoughts that William Dyson was very much the injured, innocent party in this dreadful affair, whilst his wife was the insane murderess, are now beginning to tilt in the opposite direction. Soon after her conviction, Mary Ann’s father retired from the police in Ireland and he went with his wife and several of his children to live in Pine Street, Bradford. Why Bradford, we cannot be certain but William Dyson had mentioned in a letter of that year that he was living and working in Shipley so it appears that Mary Ann’s father wanted to be near to where he was ……..and probably to keep an eye on him.

What is apparent is that there was certainly a lot of ill-feeling between William and his father-in-law, especially as William had virtually disowned his wife since the murders and, I suspect, because Archibald was monitoring many of William’s movements, and no doubt, his philanderings. Soon after William had written to Mary Ann for the first time in six years, her father also wrote to her. In a letter dated 17th December 1871, when Archibald mentions William, he only ever refers to him as DYSON and never calls him by his forename. He is certainly angry in his tone and one senses that there is no love lost between the two of them. Despite this animosity, William must have visited Mary Ann’s father around that time because he informs Mary Ann ‘as for Dyson coming to my house, it was all on account of you, AS I NEVER WANTED TO SEE SIGHT OF HIM.’

It is quite apparent that her father was worried that if Mary Ann was released, William would force her to emigrate with him and her father didn’t want to lose sight of her yet again. He wrote, ‘Dyson said to your mother that if you were liberated, you and him would be together again and would leave the country. It is not my wish that you would take up with him’. Archibald then tells his daughter that Dyson ‘has taken up with another woman and they have a five year old son together.’ He adds that, ‘Dyson has a different story to tell every time we speak,’ insinuating that William is telling lies about what he is doing now and of his future intentions. Her father concludes the letter by wishing her a Merry Christmas and hopes that it will be the last one that she spends in Broadmoor.

In early 1872, Mary Ann’s father made a 2nd application for her freedom, asking for her to be released into the care of himself and one of her brothers. Following this application, the Home Office asked the chairman of the Broadmoor Asylum to provide a report on Mary Ann for the Home Secretary, who would make the ultimate decision. The Home Office queried why Mary Ann should be released to her family and not to her husband and enquired if there would be any special dangers in so doing as William was still the legal next-of-kin, whether her mother and father liked it or not.

Trying to get Mary Ann released was in full swing but the family were desperate for her to be returned to them, and not to William. Even Rev. Thos. Hayne, vicar of St. Matthew’s got involved. If you recall, this was the man that wrote in the burial register ‘these two children were murdered by their mother’ but he appears to have changed his tone in the ensuing years. Dr. William Orange, the Superintendent at Broadmoor had asked the Rev. Hayne to make enquiries around Rastrick about William, so he is getting the local vicar to do some snooping for him. In his reply, the Rev. Hayne didn’t hold back in his damning condemnation of William’s irreverent lifestyle. This provided some supportive mitigation, though a bit late, as to why Mary Ann had carried out the murders of her children. The letter stated, I beg to inform you that I have made every inquiry respecting Wm. Dyson. I find he is living with another woman and he himself states he is married but whether this is true I cannot tell. Rev. Hayne said that he had asked the Rastrick Constable to make inquiries about Dyson and he had learnt that Dyson had once tried to get married again, despite still being legally married to Mary Ann. (However, we now know that he hadn’t married anyone at that time). Rev Hayne added, one thing is certain, that Wm. Dyson is a thorough scoundrel and I have little doubt that it was owing to his wicked conduct that his unfortunate wife was driven to desperation as even during her trial, whilst the poor woman’s life was pending, he was seen in company with prostitutes by many people in this township.

Two days after Rev. Hayne’s letter to Dr. Orange, Archibald Thompson again wrote to Mary Ann after she had also posed some questions about her husband. Her father told her, ‘Your husband has left Halifax, I do not know where he is gone to. Her father goes on to say that ‘myself and your brother have a good home for you as long as we live. If your husband never looked after you, we will care for you, for you were worthy of it.’ Archibald thanks God that Mary Ann’s health and mind had been restored and says that he has once more sent a petition for her release.

Upon receipt of this latest application for release, Mary Ann was subjected to yet another assessment by the medical staff at Broadmoor because there was no reason to keep her now, if she was declared sane. From the questions and answers in the assessment, it is clear that William Dyson NEVER visited his wife during the whole time she was in Broadmoor and had not contacted her again after his two letters in November 1871, when he said he would go and visit her and wanted her to emigrate with him.

The results of the Broadmoor assessment were forwarded to the Home Office whereupon, a Release Warrant was signed by the Secretary of State, the Rt. Hon. Henry Austin Bruce, for her conditional release. It was dated 13th of March 1872.

A further letter from the Home Office to the Broadmoor Asylum, dated the 18th March, confirmed that Mary Ann Dyson was to be released into the custody of her father, ‘Archibald Thompson of 16 Pine Street, Bradford, Yorkshire who has undertaken to receive and maintain her’. – so Mary Ann was released to her family on the 25th March 1872 and not to her husband. This was more than likely as a result of the evidence of his bad conduct, though another factor could have been that no-one knew at that time, where he was.

It would have been hard for Mary Ann to adapt to her new surroundings after spending almost eight years in a lunatic asylum. She no doubt received a tremendous amount of love and support from her family to help her settle back into life’s routine. Four months after her release, Mary Ann’s brother, Peter Henry Thompson married Anne Rogan in Bradford. It was an occasion that Mary Ann would have no doubt attended and an event that must have introduced some sense of normality back into her life. However, less than twelve months later, tragedy struck. Her beloved father, Archibald, who had given so much time and effort to get his daughter released, died suddenly at their home in Pine Street on the 10th June 1873. His death was recorded in the Bradford Observer on the 14th June with a simple entry in the death announcements column.

This was almost certainly the catalyst for the next chapter in the lives of the Thompson family. With their father gone, they had to decide what their next move would be. Did they want to remain in Bradford or should they return to Ireland? There was third option open to them however, as Archibald had two children who had previously emigrated to America and were still residing there. They chose the latter option and decided to emigrate to America. As the move came about so quickly, I suspect that this was something that had previously been discussed or even planned. It is more than likely that Archibald had intended to travel with his family but his sudden tragic death put a stop to that as he passed away just prior to the departure date.

I have not found the actual passenger records but it would appear that Archibald’s wife, Mary, his sons, John and Robert and daughters Mary Ann, Margaret and Isabella made the journey. Isabella’s husband, William Kelly and their two sons, John and Michael Kelly also travelled whilst Mary Ann’s brother, Peter Henry, followed them eleven years later in 1884.

The family chose to make their new home in the Philadelphia area of Pennsylvania and after all that the family had endured, one would hope that they lived happily ever after but things never work out as planned do they ? Soon after their arrival in America, Mary Ann was taken ill. Just as she was about to make a new life for herself, Mary Ann could not recover from her illness and she passed away on the 10th December 1873. She was buried at the New Cathedral Cemetery in Montgomery County.

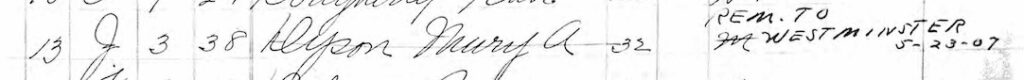

The above photograph shows the entry from the burial register at the New Cathedral Cemetery, referring to Mary Ann Dyson. If you look on the right of the entry, it states ‘REM. TO WESTMINSTER 5-23-07’. This refers to the remains of Mary Ann being removed from this grave, almost 34 years afterwards, but why?

Mary Ann’s mother, Mary, died in Philadelphia in 1885 and was buried in the same grave as Mary Ann but both remains were exhumed in 1907.

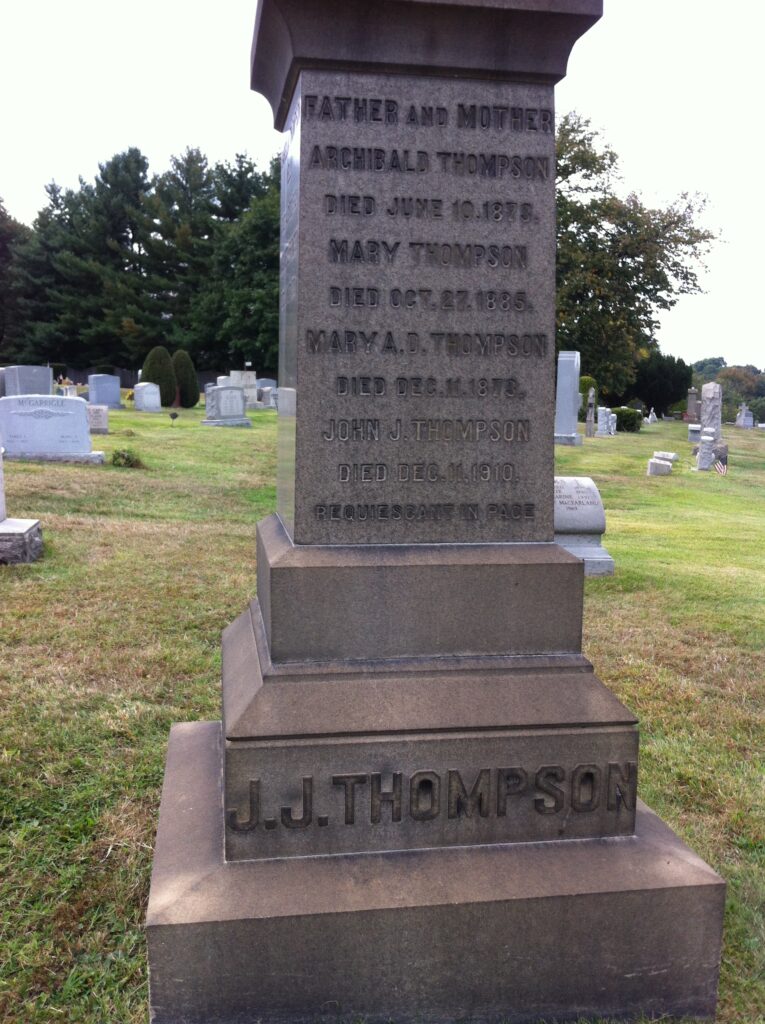

The reason for this was that the New Cathedral Cemetery became full. This resulted in the opening of a new cemetery at Westminster in 1895. As subsequent family members died, they were interred at the new cemetery and in 1907, the family requested that Mary Ann and their mother be also buried in the family grave at Westminster. The request was approved which resulted in the large family grave at Westminster, shown below.

It is interesting to note that the name of Archibald Thompson is on the gravestone, despite the fact that he died in Bradford and never visited America. Also, you will see that the family have named Mary Ann as MARY A. D. THOMPSON. This suggests that the family did not want the name of DYSON associated with their family, after all that had gone on in the past.

There are descendants of the family that remain in Philadelphia to this day under the names of THOMPSON, DUFFY and KELLY, to name but a few, but how many of them are aware of this story I wonder?

That concludes Mary Ann’s story, but what became of William Dyson. We learned from Mary Ann’s father, Archibald Thompson, that William Dyson had been to America and that he had also fathered a child to another woman but I don’t know what became of them. It appears that he deserted them, as he did his wife, Mary Ann. What we do know is that William went to Liverpool where there were Dyson family connections. He met a lady called Ann Parkinson. Both of Ann’s parents had passed away between 1871 and 1873 and then William’s own father passed away in Rastrick on the 20th June 1875. He was buried at St. Matthew’s Church and was laid to rest in the same grave plot (Line 30 Plot 4) as his two murdered grand-children.

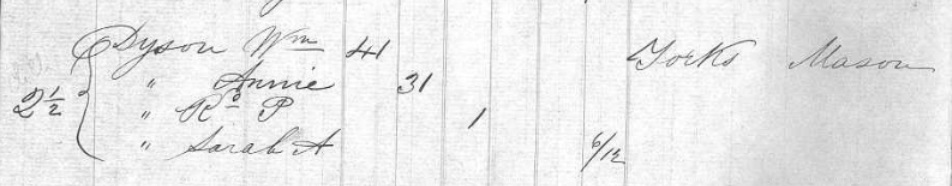

In 1876, Ann Parkinson discovered that she was pregnant and the couple decided to get married in Liverpool in October that year. I assume, but don’t know, that William Dyson had been made aware of his former wife’s death in America in 1873, and this meant that he could legally marry again. Their first child, a boy, was born in January 1877 and was named Richard Parkinson Dyson. Their second child, a daughter, was born in February 1878 and was named Sarah Annie Dyson. After the tragedy of losing his two children and first wife in such horrific circumstances, ironically, William once again found himself with a wife, a son and a daughter.

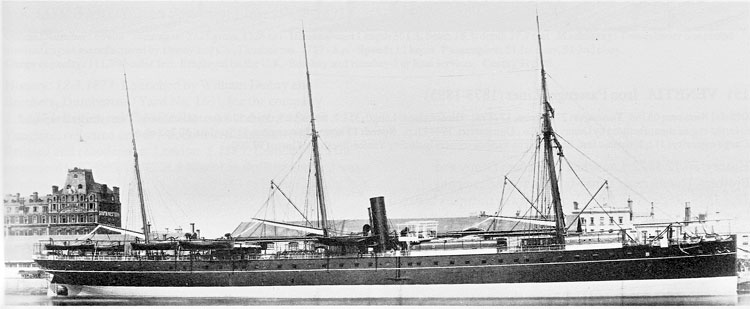

William and Ann Dyson made the decision to emigrate but it wasn’t to America, where he had visited previously, but to New Zealand. They sailed from Plymouth on the 10th August 1878, on a ship called the Hydaspes which arrived in Christchurch three months later, the 9th November 1878.

The couple’s third child, Elizabeth, was born in Christchurch on the 1st May 1880 but William wasn’t too impressed with New Zealand and so moved on to Australia where they arrived in Sydney in 1881. The couple went on to have a further four children. They eventually settled in Melbourne, Victoria, Australia

After what can only be described as an eventful life, William Dyson passed away on the 28th October 1900 at his home address of 310, Canning Street, West Carlton, Melbourne, Victoria (pictured below).

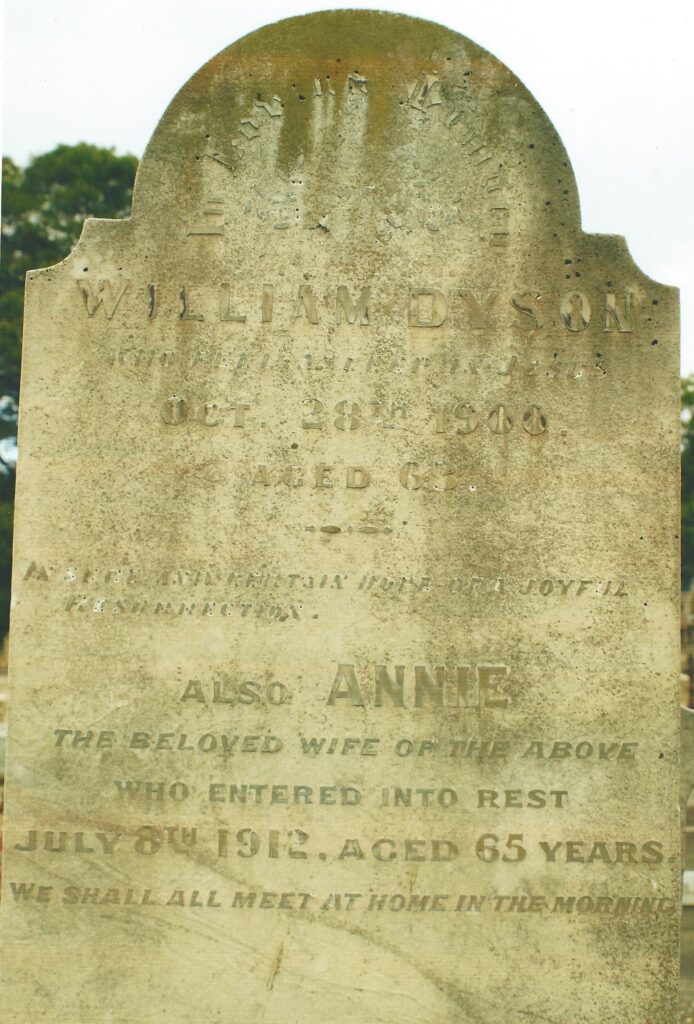

He was buried in the Melbourne General Cemetery which has to be one of the largest graveyards I have ever encountered, when I went to visit the grave. The wording on the gravestone has been somewhat eroded by the elements over the past 122 years. The inscription reads:-

IN LOVING MEMORY

OF

WILLIAM DYSON

WHO FELL ASLEEP IN JESUS

OCT. 28th 1900

AGED 63

IN SURE AND CERTAIN HOPE OF A JOYFUL RESURRECTION

ALSO ANNIE

THE BELOVED WIFE OF THE ABOVE

WHO ENTERED INTO REST

JULY 8th1912, AGED 65 YEARS

WE SHALL ALL MEET AT HOME IN THE MORNING.

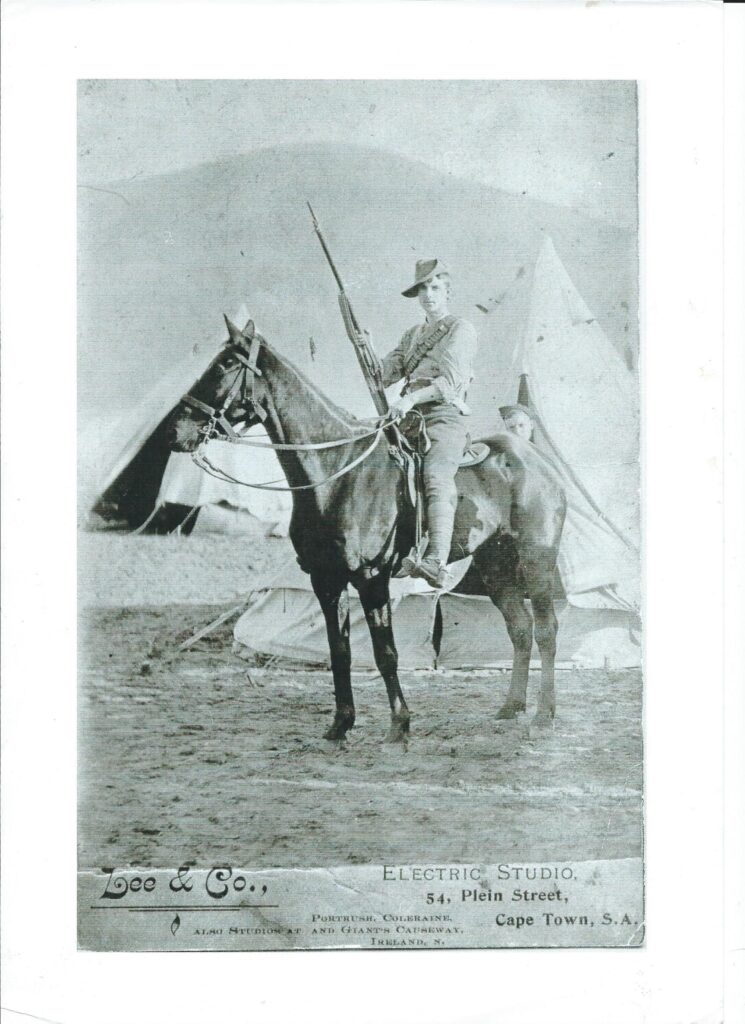

I would just like to give some mention to William’s eldest son, Richard Parkinson Dyson, who also had an interesting life. He fought on the side of the British with Lord Kitchener’s Horse in the Boer War in South Africa. He was a diver for the navy for several years and then joined the Australian Army and fought in the 1st WW. He was killed just before the end of the war on the 10th August 1918 whilst carrying a Lewis Gun into its emplacement. Richard is shown on the picture below with his Boer War medal and posing with his wife and two children.

Richard had married in 1902 and had three children at the time of his death, one son and two daughters. One of the daughters produced a son, Norman Barnden b. 1935 with whom I have been in contact for several years.

When I first contacted Norm, neither he nor his brother had any idea about William Dyson’s early life or that he had married previously before emigrating therefore they were quite shocked at the story you have just read. After hearing of his great-grandfather’s exploits, Norman said in true Aussie fashion, “Wow, that’s bloody wonderful, I always suspected that I came from bad stock”.

So that concludes the story of the Rastrick Murders, a sad tale that happened in the little village of Rastrick but resulted in other generations of their families, now living in Australia and America, many of whom are totally unaware of their amazing family history.

I’d like to finish with a poem written by John Sheppard of Rastrick. It refers to Doctor Henry Pritchett, the man who gave evidence at the trial of Mary Ann Dyson in Leeds in 1864 whilst he was only 32 years old himself. He was criticised by many after the trial for defending Mary Ann because they thought that she should have hung for her crimes and especially after she was declared sane and then released from Broadmoor, just 8 years later.

Dr. Henry Pritchett (1832 – 1894) lived at The Poplars, Rastrick Common, Rastrick. As discussed earlier, Dr. Pritchett argued that Mary Ann Dyson was not guilty of wilful murder because she was suffering from Impulsive Insanity at the time of the offence. There was much scepticism as to its validity at the time and was a last resort plea, when all the other evidence suggested that a person had committed a crime. Despite this, many doctors felt that there was something that affected the minds of some mothers of very young children, which triggered acts that were not normal and out of character. The Infanticide Act 1922 effectively abolished the death penalty for a woman who deliberately killed her new born child while the balance of her mind was disturbed as a result of giving birth. Further Acts in 1938 and 1939 revoked the earlier Act, but introduced the idea that Postpartum Depression was legally to be regarded as a form of Diminished Responsibility. In more recent times, such behaviour would be regarded as Postnatal Depression which the NHS states can be triggered by such things as:-

- a history of mental health problems, particularly depression, earlier in life

- a history of mental health problems during pregnancy

- having no close family or friends to support you

- a difficult relationship with your partner

- recent stressful life events, such as a bereavement

- physical or psychological trauma, such as domestic violence

Some of these triggers appear to be applicable to Mary Ann Dyson and if she had hung for her crimes, we would probably now consider that it was a miscarriage of justice but I’ll leave you to make your own decisions. The poem reads:-

I don’t think I did anything wrong.

She was a lass who didn’t belong

In lists of those with murderous intent,

Wicked menfolk of criminal bent.

Beyond all doubt she was most willing

To take all the blame for the killing

Yet because of me she did not hang.

Of regrets, I’ve not the slightest pang –

What mother, sane, would have killed those two?

It’s nothing that healthy people do.

My own dear wife would soon be with child

Though she’s not poor and she’s not exiled,

Like Mary Ann, we are comers-in.

We are distant from our kith and kin.

My Maria is of a similar age:

Her husband, though, earns a surgeon’s wage.

As a physician I am aware

Of the burdens, that mothers must bear.

For Mary Ann the stress was too great.

Now for the children it was too late,

But it was my duty in the court,

In her hour of need, to give support.

Could be “Hanged by the neck until dead”,

Or could be “We understand”, instead.

“Impulsive insanity”, I said,

“That’s how these children came to be dead.”

The evidence that I gave in court

Was not in vain, did not count for nought.

A few brief years and she’s declared sane,

The doctors say she need not remain.

Now she’s released, free to go her way,

It’s to be expected some will say

That it was unjust I had my way,

That I led those twelve men true astray.

Wherever she’s gone I wish her well.

What will be her fate I cannot tell,

But when I go to my bed at night

I know for certain that I was right.

I had to say what I had to say:

Yes, it really was the only way.

One day the world will agree with me,

What the Rastrick people then could see

Deserved a wider recognition –

They’ll give a name to this condition.