THE CALDER & HEBBLE NAVIGATION - TAG CUT

Tag Cut is a 500 metre section of disused canal in the Cromwell Bottom Nature Reserve. It lies at the bottom of Rastrick’s Strangstry Wood and was designed as a short cut across a meander in the River Calder. Gone are the great wooden flood lock gates at the western entrance of the canal. Gone is the beautiful lock-keepers cottage, bridge and lock gates at the eastern end. Part of the old waterway is now blocked whilst the remainder is deep and dangerous silty mud. But why was Tag Cut built and why does it merit a section in this historical website? To start the story of Tag Cut, we first have to look at how and why the navigation came to the area in the first place.

WHY THE CANAL CAME TO THE TOWN

In the mid 1700’s, the Industrial Revolution was moving rapidly through the manufacturing industries of this area, in particular, textiles. This saw a major switch from the people working in their homes to working in purpose built mills. A better road infrastructure was required to deliver larger quantities of raw materials and to then distribute the finished products around the country. Most roads were in a poor state and the superior highways had expensive tolls, however, a horse and cart was limited in the quantities it could carry.

Quarrying was a major industry in this area and it was difficult to move large stone items by road. It made economic sense to develop the rivers and make them navigable in order that goods could move easily between places where they were required. A canal network that linked the country was deemed to be the answer, using large barge boats to move products in greater quantities than ever before. Water transport was about one sixth of the cost of land carriage, so there was good reason for developing the navigation.

Following the success of the Navigation from the east coast to Wakefield, the towns of Halifax, Ripponden and Elland petitioned Parliament for the Calder to be extended from its junction with the Aire & Calder to Halifax. Their argument was that it would help them trade more easily with London and other major places and also help to force down the toll road costs. John Eyers of Liverpool first surveyed the route in 1740 and along with Thomas Steers, came up with a plan to bring the navigation as far as Brighouse but the Act of Parliament was defeated at the Committee stage.

Why was it defeated? Three reasons mainly:-

- There was opposition from landowners who thought that their land would be flooded

- From the owners of fulling mills who suspected that the canal would reduce the water supply to the rivers and turn their mills idle.

- There was also opposition from supporters and shareholders of Turnpike Trusts.

In 1756, a meeting was held at the Union Club in Halifax where it was decided to invite John Smeaton to make another survey. He said he was too busy with the Eddystone Lighthouse but after another invitation in June 1757, he agreed to attend in the autumn. Smeaton looked at Eyres and Steers plans from the 1740’s. He asked why the plans only took the navigation up to Brighouse and why it hadn’t been extended up to Halifax. He was told it was difficult due to:- ‘the great difference of level, scarcity of water, rockiness of the channel and the great number of fulling and other mills situate on this Brook’.

Smeaton said that a navigation could be built without much damage to the mill-owners in comparison to how they would benefit. He completed his survey in October and November 1757 and spoke to a meeting at the Talbot Inn, Halifax in the November where he showed his plans to dredge shoals, build some short cuts and locks to overcome the 178 ft rise from Wakefield to the mouth of the Halifax Brook at Salterhebble. In December 1757, a mill and landowners meeting approved Smeatons plans and following discussions with navigation engineers in Lancashire, a Bill was passed in June 1758 to make the Calder navigable from Wakefield to Sowerby Bridge at a cost of £2,075.

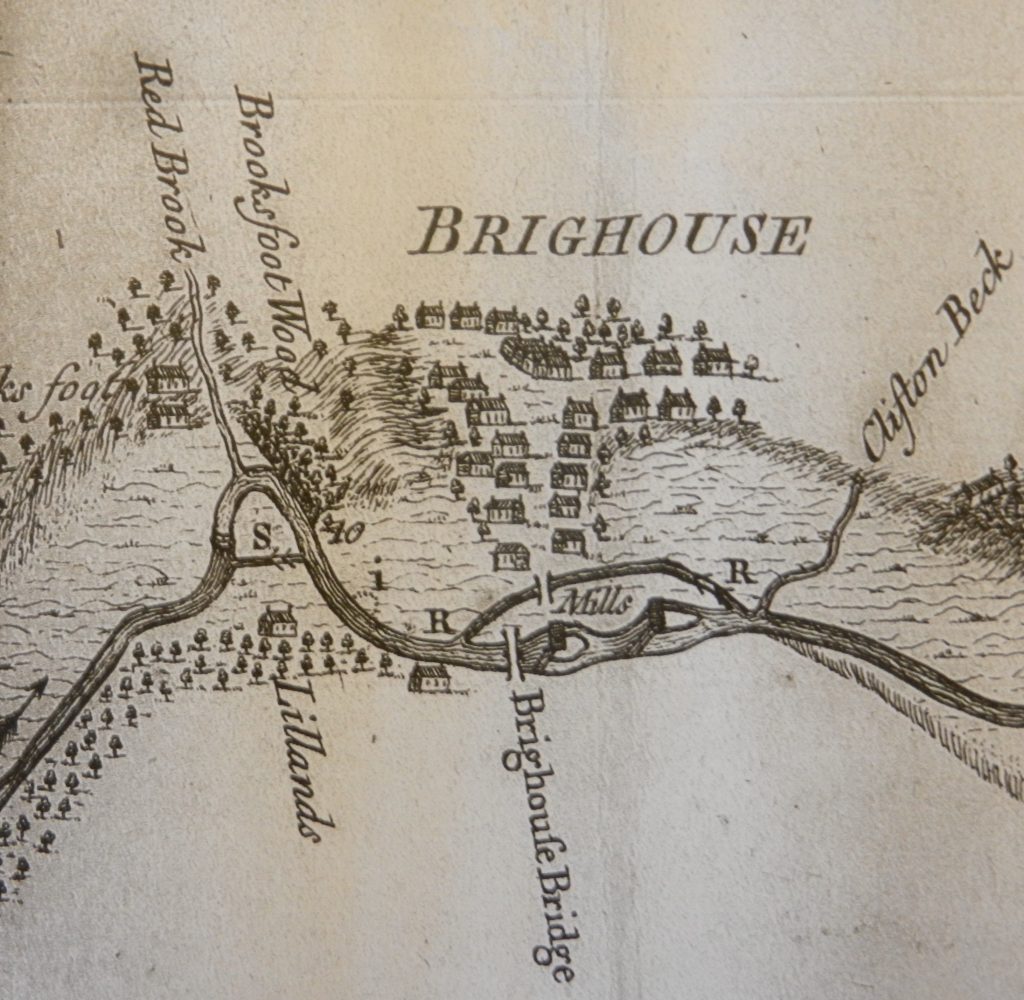

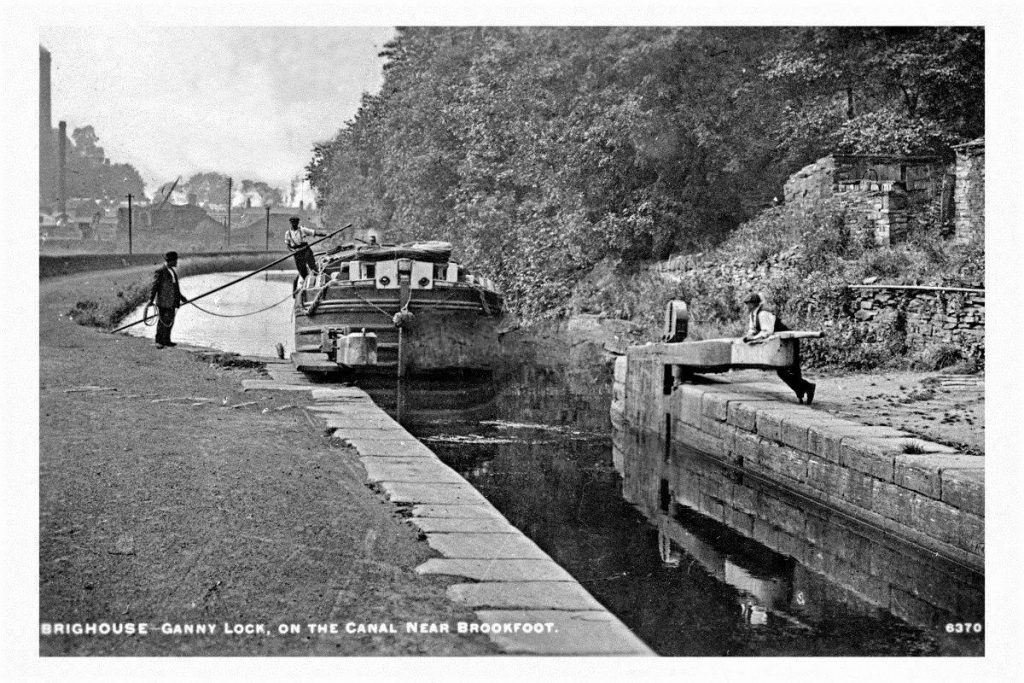

As the canal approached Brighouse from the east, there were and still are, two weirs located near to the two road bridges over the Calder. The weirs had been there for many years and supported the mills built upon them so a canal was built to bypass the weirs, similarly to how a ring road by-passes town centres nowadays. The canal came as far as Ganny and then led into the river through where the lock-keepers cottage is now located. Mr. C. Jessop stated this when he spoke at a lecture in Brighouse in 1892 but in recent years, I have spoken with the owners of the cottage. They kindly took me down into their cellar where the walls of the old lock form part of the foundations of the building. The curved stone walls and the grooves where the old lock gates once stood are clearly evident and prove the theory that the entrance to the river travelled in virtually a straight line from Brighouse. From Ganny, the navigation went a little further upstream before cutting across the fields at Lillands towards Brookfoot. It then continued up-river towards Elland and the entrance to Tag Cut.

The fields at Lillands have always been susceptible to flooding and in times of great rains, such as Christmas 2015, this area was totally under fast flowing water at a depth of several feet. The early canals, as this most certainly was, didn’t have lock gates on the upstream end. If the river flooded, the flood water would enter the canal, bringing all the debris with it. In low laying areas such as Lillands, the whole of the canal could be totally swamped. The raised earth banks at the side of the cut were liable to be washed away and this is exactly what happened. Just as the canal was ready for opening in October 1767, a great flood swept away all the works and made the canal un-navigable and so all the digging had to be done again.

Smeaton had left the project in 1765 following a dispute and he was replaced by James Brindley but he too resigned after just one year. The month after the floods, Smeaton returned once again. Whilst the repairs were being carried out he suggested raising the banks of the cut even further and also suggested the new idea of introducing flood gates at the entrance. This would cost a further £3,000 but his advice was ignored and just as the work was being completed, another flood hit in February 1768 with the same result as before.

By this time, the Navigation Company had spent £64,000 of which £56,900 had been borrowed as only £7,100 had been raised in tolls. The company had to go back to Parliament for another Act to introduced, in order to allow them to borrow further money. Whilst this was going on, the lock gates were padlocked at one end and the entrances where the new lock gates were going to be placed, were dammed up to prevent further damage to the cut.

Following the passing of the 1769 Act of Parliament, a new company was born, the Calder & Hebble Navigation Company. They were given the right to raise a further £20,000 through a share issue and so the cuts were re-opened and the work suggested by Smeaton was completed. This meant that the cuts now had lock gates at each end for the very first time. The river-lock gates at the upstream end would mean that the canals were safe from flooding unless the high bankings were breached by flood waters. This was something that was always possible at Lillands. By the 1770, the navigation was fully navigable all the way through to Salterhebble and beyond to Sowerby Bridge where the intention was to link up to the Rochdale Canal thereby allowing a network from the east coast through to the west, an 18th century version of the M62 motorway.

THE FLOODS

The flooding danger at Lillands was obviously a concern to the Navigation Company owners because in 1780 they decided to create the current canal cutting from Ganny to Brookfoot. This involved building new lock gates at both ends of the new section and making up the former entrance into the river at Ganny. The new canal was then cut below the sheer rockface under the Elland Road, around to the Red Beck and then through some lower lying ground at the rear of Brookfoot corner towards Brookfoot itself. This section of canal is about five metres above the river level therefore provision was made for overflows so that if the river flooded into the canal near Brookfoot, it could drain back into the river again on its journey down to Ganny.

By ascertaining that this new cut was built in 1780, we can assume that the lock-keepers cottage is of the same date. There are no deeds as the cottage was built by the Navigation Company on its own land. Despite the plans to eliminate flooding of the canal, no-one could have expected the deluge of rain that came over Christmas 2015 resulting in the now famous Boxing Day Floods.

The canal was inundated with water that predominantly came down the Calder from the Todmorden, Hebden Bridge and Mytholmroyd areas. The Calder burst its banks in several locations which turned the canal into a flowing river. A van was swept into the canal from the Colliers Arms car park on Elland Road. It floated over the lock gates at Park Nook before partially sinking near to Lower Binns.

A moored narrowboat was overcome by the flow of water and became submerged. The ancient Crowther Bridge was so badly damaged that it had to be demolished and completely rebuilt, as did a section of the Elland Bridge which then caused traffic problems for a further twelve months. At Brookfoot, the water flowed down the 1780 section with such great force that the overflows could not cope with it. The pressure of the water against the wall between canal and river was too great that a large section tumbled into the river below. This old stone wall with half-round cap tops has now been replaced with…… a wooden fence !

When the waters subsided, the towpath was covered with 15 centimetres of silt and mud. The flood water had poured through the lock-keepers cottage, creating a waterfall at the end of the cottage’s beautiful gardens. This caused further damage to stone walls and ruined all the hard work that had been done to create the gardens. A waterfall formed over the lock gates which cascaded into the lower section of canal. This then surged through to the Brighouse Basin before re-entering the swollen river. It left behind extensive flooding around Briggate, the likes of which hadn’t been seen there since 1946.

PHOTO’S OF THE 2015 FLOODS

BROOKFOOT

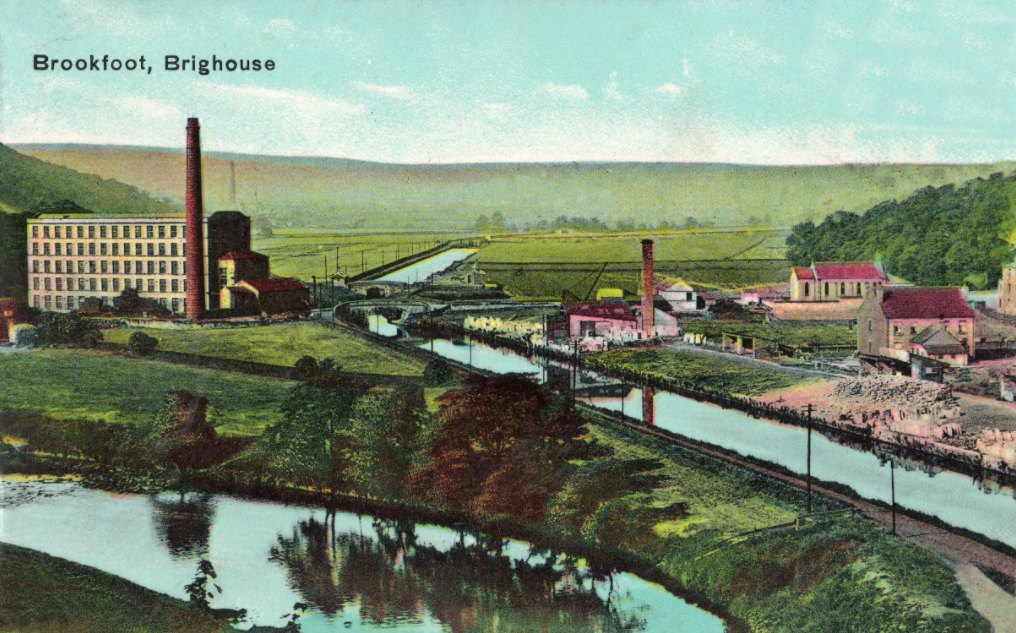

Returning to the history, once the section of canal between Ganny and Brookfoot had been completed around 1782, a wharf was built to service the Southowram stone quarries and coal mines. Loading the barges at this location was much easier than taking their heavy cargo by road to the canal basin in Brighouse or across boggy ground to the wharf at Tag Cut. The wharf was also used for off-loading coal for use at the Brookfoot mills which many will remember as the Bradford Dyers Association or just simply B.D.A.

The coal was brought upstream from the coalfields near to Castleford via the Aire and Calder and then into the Calder & Hebble. At its peak, the generators at Brookfoot were burning one hundred tons of coal per day and so the company bought their own barges to save money on transport costs.

A public house known as The Wharf was built around 1833 to cater for the dock workers although in more recent times, the name was changed to the Red Rooster.

The main top photograph shows the river on the left and the canal on the right, looking up towards Brookfoot Mill. The wharf can be clearly seen on the right of the canal with piles of stone and other materials waiting to be shipped to their destination. This photograph was taken in 1918, towards the end of the canal era but the 1893 ordinance survey map of the area shows static cranes located on the wharf which had been erected in the days when the canal was still very busy with traffic. What is interesting about this hand coloured photograph is that the land on the right of the canal in the distance are green fields. This was before the sand and gravel works started which left huge craters in the ground that now form the ski lake and the fishing lake. The land behind the mill on the left of the canal is now the Cromwell Bottom Nature Reserve and covered in trees.

At Brookfoot, the canal re-entered the navigable section of the River Calder and continued west towards Elland. The flood-lock gates had to be very strong to withstand the great water pressure as the river flowed down towards Brighouse. The first photograph on the right shows a recent view of the old gates, which are now rotting away and will become a distant memory before much longer. The land between the river and the gates has been filled in to keep the river water back.

Immediately opposite the lock gates was another wharf that served the quarries at Lillands. It was a wooden structure and extended out into the river. Stone was brought down an inclined delvers track from the quarries where it was loaded onto the boats. It was then taken down the canal to the east coast ports where it was loaded onto larger vessels and transported around the country or abroad.

The second photograph on the right shows the old delvers track heading down to the river bank from Lillands on the Rastrick bank of the river. It is in remarkable condition, probably because that area of land has been inaccessible for many years and can only be reached by boat or by trespassing on private or railway land. The track runs down to the river at exactly the same angle as the row of wooden posts that used to support the wharf. The posts can only be seen when the river is very low.

I am unable to put a date on this wharf and nothing appears to have been written about it in any of the history books relating to the canal or quarries. I am certain that it predates the railway which arrived in 1840. As the quarries were on the other side of the railway some kind of crossing point for the stone wagons had to be created. The wagon drivers and carters would no doubt be well aware of the railway timetable.

The track is actually shown on the left of the 1834 Myers map (3rd picture) upon which the proposed route of the Manchester and Leeds Railway is shown in a pink line. Delvers tracks are also shown on the Southowram side of the river. Most of these still exist and this map is very accurate. I have a friend who has overlaid this map onto Smeaton’s map and then overlaid both of them onto a modern OS map and the similarity between them is quite remarkable.

The fourth and final photo shows the remnants of the wooden wharf which was visible after a period of very little rain during the summer of 2016. You can see the angle at which the posts run into the river. Being at the same angle as the track, it would make it easier for the cumbersome wagons to go onto the jetty and offload the stone before clattering back up the hill on the return journey.

WHY TAG CUT WAS BUILT

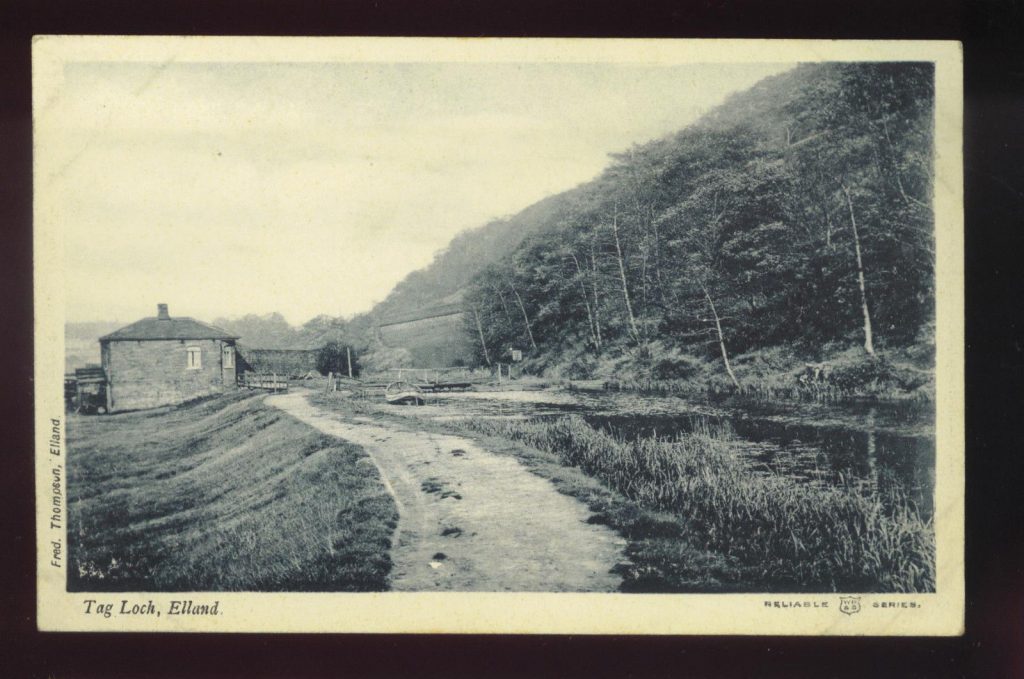

From Brookfoot the river once again becomes navigable as it continues towards Elland until a point where another meander or loop has formed in the watercourse. Here the river bed is rocky and shallow and it would be impossible for boats to bypass when the water is at a normal level. Added to this problem, around the Elland side of this meander was yet another weir. The only way to bypass both of these obstacles was to build another short section of canal. This area was known as Tag Hole and the cut became known as Tag Cut.

Where does the name ‘Tag’ come from? Legend has it that the area is haunted by a headless ghost named Tag who drives a carriage pulled by a two-headed horse down Tag Cut. The name of Tag derives from a secret passage at Elland Old Hall where there was a room named Tag Chamber.

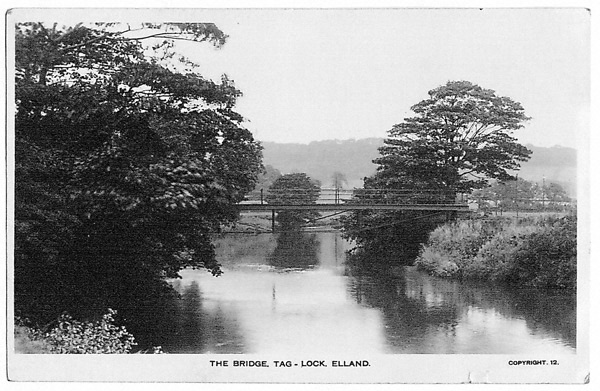

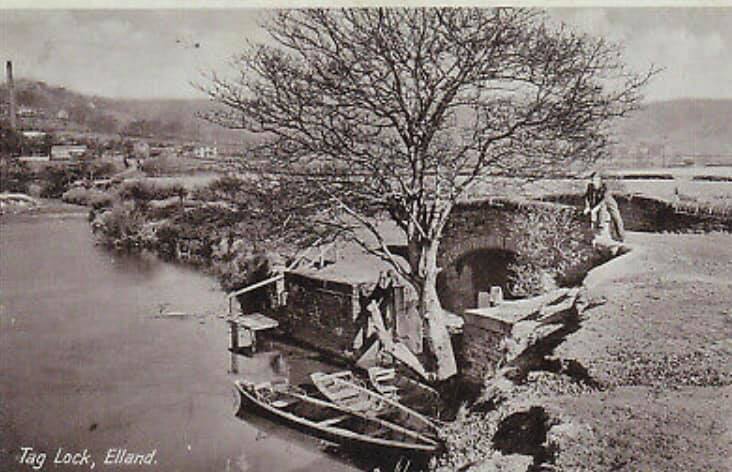

The towpath is on the right hand side of the river when travelling towards Elland and a bridge was therefore needed to transport the horses across to the other side and continue up Tag Cut. The bridge is long gone but the stone support is still evident on one side of the river banking. Lock gates and a lock-keepers cottage were situated at the river entrance which led immediately to Tag Cut Wharf.

Some historians have made reference to Tag Cut being a ‘white elephant’, stating that it was never really used but my research proves this to be incorrect. My main argument is that the current section of canal between Brookfoot and Elland was built between the years 1806-1808. We know that the navigation reached Sowerby Bridge by 1770 therefore the only route through to that place for 38 years was via Tag Cut.

The top photograph to the right shows the old bridge over which the horses travelled to get to Tag Cut. Once the towing horse had crossed onto the opposite bank, the barge was towed into the entrance of the lock where the water level was raised to lift the boat up about two meters to the level of the Tag Cut canal.

The lock-keepers cottage was located on the right, between the river and the canal, very close to where a large electricity pylon now stands.

The lock itself was a wonderful construction but although the stonework is still evident, the lock gates are long gone and have been replaced by a permanent brick wall. In the centre of the wall is an overflow which helps to maintain a constant water level.

Some people have attempted to block up the overflow in the brick wall by various means. This is done in order to raise the level of the water behind the wall but then other people come along and remove the obstruction because they have deemed the overflow to be at the correct height for the required water levels. It is a constant battle that no-one ever wins.

There doesn’t appear to be any need for the overflow in the brickwork as the original stone cobbled overflow that runs down one side of the old lock is still in perfect working order. When it is in full flow, the overflow washes the fallen leaves and other debris into the river and it then shows off the beautiful workmanship that has survived for 250 years. It deserves to be seen but the Japanese Knotweed that grows close by makes it almost impossible to access, especially in the summer months. The eastern end of Tag Cut receives fewer visitors every year. This was once a haven for Field Lane and Oaklands kids to swim but it was quite dangerous.

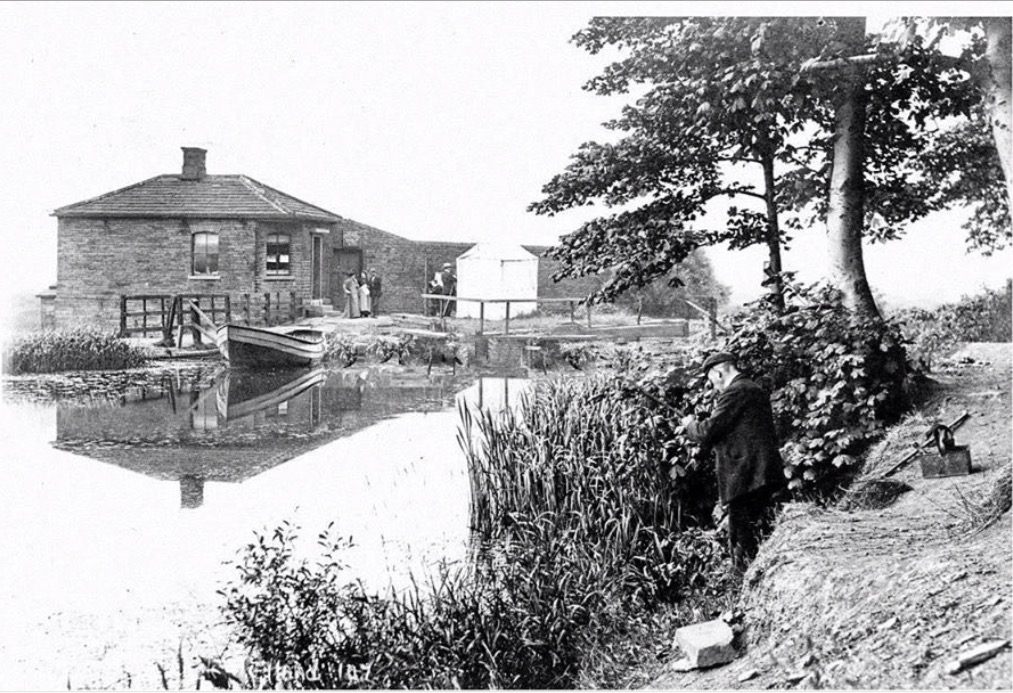

The lock-keeper’s job must have been quite interesting, especially in this location. It is quite a way to the nearest habitation therefore in the days before public transport and motor vehicles it would have been very difficult to ’nip to and get the shopping’. So how did the lock-keeper and his wife sustain themselves, especially if they had young children. The area around Tag Cut is now surrounded in trees but in those days, the area of land between there and Elland Road was good quality farmland where sheep and cattle would graze.

I expect the lock-keeper would have had a cottage garden where he grew his own potatoes, vegetables and salads. He may even have had a milking cow or even a few pigs and hens. No doubt he got to know the watermen who passed by on a regular basis. This type of local regular through traffic would bring him other items as required. He could even barter some of his fresh produce in exchange for coal or other favours. He would certainly have owned his own boat, an example of which can be seen on the photograph above.

The above oil on canvas painting by George H. West dates from 1903 and was gifted to the former Brighouse Borough Council in the early 1970’s by Richard Woodhouse and is currently in the Calderdale MBC collection.

The painting depicts the eastern entrance to Tag Cut. The stone lock and gates can be seen to the left of the lock-keepers cottage. The shallow waters rolling over the rocks or ‘shoals’ as John Smeaton called them in his early survey of the area can also be seen just to the right of the entrance to the cut but artistic licence then takes over as the metal bridge, which would have certainly spoiled the painting, is not shown. Without the bridge, the towing horses would not have been able to cross the river to continue hauling the boats up Tag Cut, thus creating a missing link in the journey.

Once the lock gates had been negotiated, the canal opened out to its widest point as this was the location of the old Tag Cut wharf. The stone wharf covered an area of two roods and eight perches which translates to approximately 150 square yards. The shape of the land tapers to one end therefore the length of the wharf would have been around 200 yards in length, backing up towards the hillside and railway behind.

It was here that barges were moored, loading and off-loading their cargoes. In the early days of the canal, barges often came up empty from the Aire and Calder Navigation. Upon arrival at the wharf, they loaded their boats with stone and then conveyed the load back in the opposite direction. Local farmers wanted to reclaim the weed infested land adjacent to the river and canal. They arranged with the barge owners to bring lime upstream in their empty vessels in order that could spread it on their land. The acidic boggy ground was drained and the woods were cleared to increase the amount of farming land and the lime was used to help to fertilise the poor soil. Acidic soil encourages the growth of weeds such as sorrel, creeping buttercup, nettles, dock and mare’s tail and by spreading lime and reducing the acidity of the soil, it helped to deter weeds and improve the land for other uses.

The wharf was busy with men from various trades. In addition to the stone masons, there were blacksmiths who were employed mending the chains that were used to haul the large stone blocks. They also sharpened the chisels of the quarrymen whilst joiners would be repairing broken haulage carts. Farriers would re-shoe the great Shire or Clyesdale horses whilst general maintenance men and barge loaders would be busy taking care of the cargo. Some horses would need to be fed and stabled whilst the boats were off-loaded. Some boat owners took their families with them as the barge was also their home. His wife and children would assist where possible and it wouldn’t be uncommon to see the children playing on the wharf side. There would be smells of cooking as the ‘watermen’ sat down to eat their evening meal before settling down for the night and then moving off the following morning.

There would have been several buildings, mainly built from wood but if you look closely, there are shaped stones laying on the ground. They are now covered in green litchen but must have formed part of a building at one time. This area has now returned to how it was when the canals first arrived with one main exception. The trees have returned and the area once again resembles a woodland but this land is unique. For many years it was used for the tipping of fly-ash from the nearby Elland Power Station whilst another section was a household waste site. New saplings have rooted into the fly-ash but underneath this seemingly stable ground lies vast quantities of water from various floods over recent years. The saplings grow into larger trees but the roots cannot hold them and many just fall over and die. This natural cycle adds to the nature reserve habitat.

The dead trees encourage many insects. Moths, butterflies, dragonflies and damselflies are very common in the Reserve and this has in turn attracted a large variety of birds. The area has transformed itself into a popular tourist area with walkers, cyclists and dog-walkers all enjoying the natural beauty of the area.

It is on record that Richard Brook, a Mirfield contractor and stone merchant, shipped large quantities of faced and common flags, sinks, copings, faced paving, steps and roofing slates from shipping points at Brighouse and Tag Cut. At least 1,302 tons were moved in barges between September 1791 and January 1793. He was consigning stone to London from 1792 by which time he was employing an agent there for its sale.

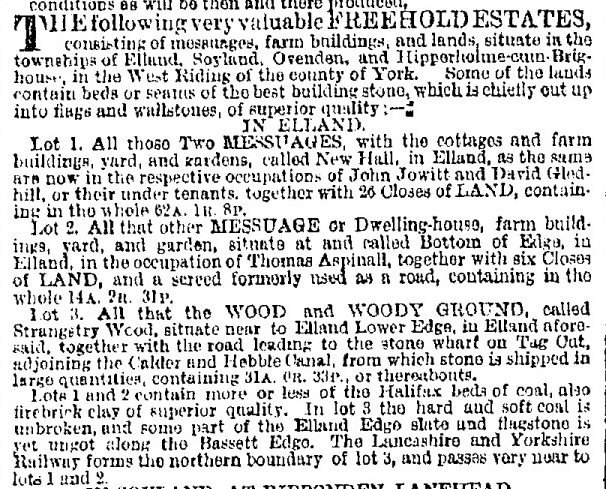

In addition, there was an advert in the Leeds Mercury on the 19th October 1867 which states that a freehold estate of land is for sale which comprises of ‘All that wood and woody ground called Strangstry Wood situate near to Elland Lower Edge together with the road leading to the stone wharf on Tag Cut, adjoining the Calder & Hebble Canal from which stone is shipped in large quantities’.

The geological history of the area around Tag Cut is interesting. It gives an insight into why certain industries such as clay, coal and stone mining became established. Walking west from the old wharf area, the water in the cut starts to change colour. It gradually turns to a bright orange colour and looking carefully, the source can be seen in the hillside.

To understand what is happening we have to journey back some 500 million years when this area was positioned at 60˚S of the equator. Mudstone was laid down from silt deposits which over time were compressed, and being fragile, the mudstone cracked under pressure as the tectonic plates moved northwards. It eventually became shale.

Move forward to 310 million years ago and the area was positioned near the equator. A large delta spread from Scotland to the Midlands and soft sandstone formed in lagoons whilst course sandstone formed the river beds. Plants and trees fell into the lagoons where the hydrogen and oxygen was forced out. This meant that only carbon remained and over millions of years it turned into coal. The orange coloured water is produced by iron sulphide which is present in the ancient shale and is flowing from old stone and coal mine workings which are now flooded.

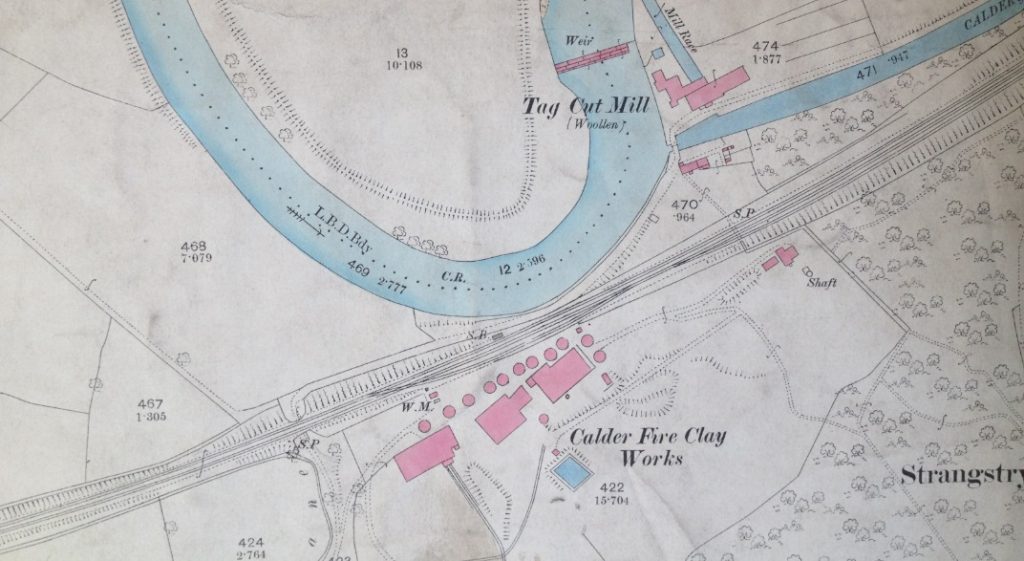

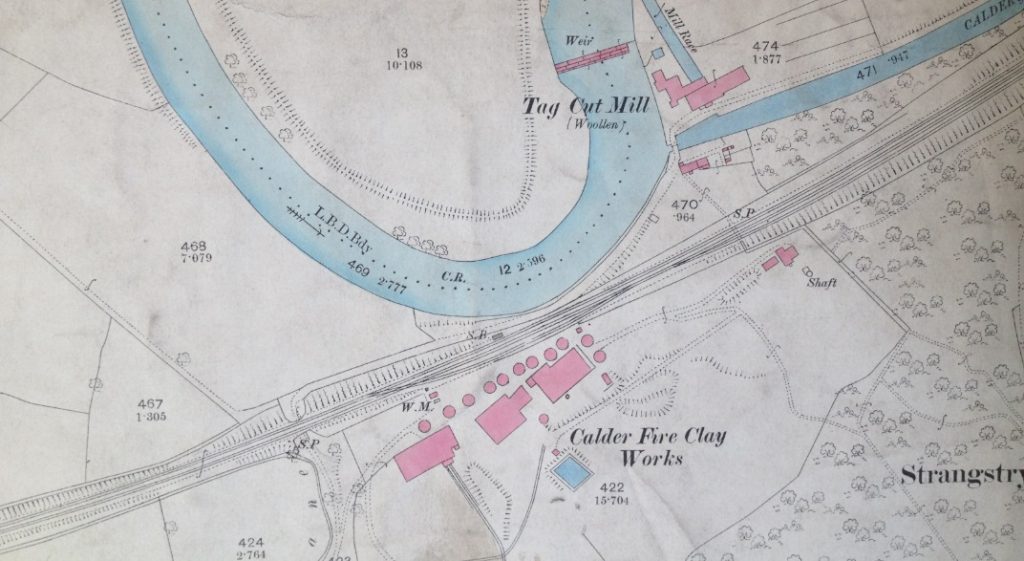

The clay deposits in the hillside were ideal for manufacturing bricks and the Calder Fireclay Company can be seen on the 1893 map. It was a huge business which had special tramlines built to deliver the clay to the kilns on the Rastrick side of the railway. In 1896, the company was owned by E.J.W. Waterhouse & Son and is listed as producing not only clay but also coal.

There were five types, coking, gas, household, manufacturing and steam coals. This area produced manufacturing coal and in 1896, the company employed forty underground workers and eight surface workers. The area latterly contained the brickworks of Samuel Wilkinson & Son who produced firebricks from the blue clay and then went on to diversify into normal brick manufacturers until recent years when they were taken over by Butterly Bricks, which closed down in 1985.

The vast stone deposits in much of the area were difficult to get from the ground. Mechanical machinery made life a little easier for the delvers in later years but on the hillside of Strangstry Woods, the early delvers found that valuable sandstone had already been exposed when the Calder Valley was created during the ice age. Delvers would literally pick out the mudstone shale from underneath the sandstone bed, which can be up to 70m thick in places. They would support the stone above with wooden stakes, working deeper into the hillside around fault lines in the rock. Upon removing the wooden supports, the weight of the stone would cause it to fall and break into more manageable sizes. Many delvers were killed whilst using this method.

With advances in technology it meant they could delve further down into the rock and create shafts. The stone would then be brought up to the surface via ladders and carried in leather harnesses strapped to the delver. Many fell to their deaths and the average lifespan of a delver was just 45 years of age. In addition to horrific accidents, many delvers died of lung and heart related diseases that went with working underground.

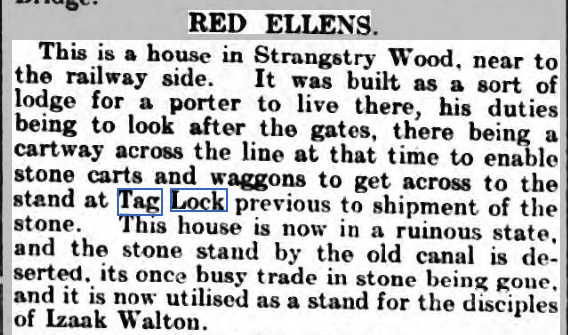

The stone was brought down the hillside to Tag Cut wharf where masons would cut stone into required sizes before being loaded onto the barges and shipped to the east coast. The coming of the railways in 1840 made it more difficult to bring stone down from the woods to the canal as delvers were forced to cross the railway lines. A level crossing was built for the purpose and was staffed by a crossing keeper. As the keeper had to be available at all times, a house was built which used to be known locally as “Red Ellen’s” after the nick-name of the widow who lived there. The house was demolished towards the end of the 19th century and hardly any trace of it remains today.

In the 1851 census, ‘Red Ellen’ is shown residing at Railway Cottage, Strangstry. Her name was Ellen Buckley and at the time she was a 37 year old widow, born in Prestwich, Lancashire. Ellen’s job was described as a Railway Gate Keeper and she had a 27 year old railway labourer, John Feather, lodging with her.

In 1861, the house was shown as Wood Cottage when Ellen had another lodger residing with her, 23 year old railway plate-layer, Richard Howarth. She remained there until after 1871.

Just in case you are wondering who Izaak Walton was, he lived from 1593 – 1683. He was the author of a book entitled ‘The Compleat Angler’ (yes, that’s how it was spelt) and is still regarded as being one of the most important books on fishing in history.

The horse drawn stone wagon was an unwieldly but strong contraption. It had massive wheels which required constant lubrication to alleviate the annoying squeaking. As you can imagine, the heavy wagons caused damage to the poor tracks therefore stone flags were laid to stop them becoming bogged down. If you go into the woods between Elland Road and Southowram, you will see some amazing examples of these types of roadways.

The quarrying industry became very popular in the middle of the 1700’s as the arrival of the navigation coincided with various Acts of Parliament that were designed to improve the streets of the capital. The St. Marylebone Act of 1756 was probably one of the first Acts but the London Commissioners were not sure where to get their stone from. They needed it to be of a certain quality, at the right price and also in great quantities. Stone from the Elland Flags fitted the bill perfectly and the Calder & Hebble was able to deliver these vast amounts to the east coast ports, where it was loaded onto larger vessels and shipped down to the London docks on the Thames.

Other towns such as York and Leeds had similar Street Commissioners and Acts of Parliament were passed in 1771 to pave, improve and sewer the streets of those places. By 1773, the commissioners for those towns had to hire their own boats to ship more stone as work had come to a standstill for want of more flags from Elland. Many roads were still using cobbles that were dredged up off Spurn Point until the 1790’s but road sett stones became popular by about 1814. These were purchased from Samuel Freeman and his predecessor, John Freeman who owned quarries in Southowram. The Freeman family was one of the largest suppliers of stone flags, slates and setts from the latter part of the 18th century.

I have researched this family who originated in Fixby before purchasing farm land at Southowram. William Freeman’s eldest son Joseph went to work in London as a stone merchant and owned wharves in Paddington and Millwall. He died aged just thirty-nine whereupon the second eldest son, William, went to London to continue the trade. He ensured that Freeman’s stone from Cromwell Bottom was used in the capital. He married into the Mowlem family who owned granite quarries in the Isle of Purbeck and Cornwall and the company exhibited at the Great Exhibition amongst many others.

In addition to paving London’s new streets, the Freemans provided stone for many London docks, bridges and roads. Their stone was used to build lighthouses at Beachy Head, Bishop’s Rock and Guernsey. It was also used for the plinth and lodges in front of the British Museum in Trafalgar Square, the Royal Exchange, the steps and landings and terraces at the Crystal Palace and the obelisk for the 1851 Great Exhibition, now erected at Chelsea College. It provided stone for many monoliths and statue pedestals throughout London. They were also involved in paving Queen Victoria Street, rebuilding Billingsgate Market, Smithfield Fruit & Vegetable market and many sewerage and railway contracts. Two members of the family left the equivalent in today’s money of £27m and £13m. Other family members left vast fortunes in their estates upon their deaths. The company went on to oversee contracts such as Admiralty extensions including Admiralty Arch 1906-14, New Scotland Yard 1908 and re-fronting Buckingham Palace 1913.

The Freemans who stayed behind created stone staiths along this stretch in order to load their barges and take the stone down to London. I believe that they were influential in this particular section of the canal being built between Brookfoot and Elland as it suited their business, being much nearer to their quarries than Tag Cut Wharf. Hence the navigation at Cromwell Bottom is known as Freeman’s Cut. The family owned Brookfoot Wharf and they made donations for the building of the church and school at Brookfoot.

In addition to Freeman’s Cut there was also Freeman’s Wood adjacent to Elland Road and a Freeman’s Mill at Brookfoot where the lock is called Freeman’s Lock on early OS maps. This was a very important family in the early days of the quarrying industry and assisted greatly in putting the Elland Flags on the map of the finest stone-mines in the land.

A major blow came to the stone trade in this area when the Chester & Holyhead Railway opened in 1850. This opened up the North Wales blue slate trade to cheap competition with the Yorkshire grey slates. The Welsh slates were cheaper and lighter in weight and easier to fix. As a result, the Yorkshire stone roofing trade disappeared very quickly except for very local use and some repair work.

The local stone setts which were used for road surfacing then came under competition from the harder setts which came from Leicestershire and Aberdeenshire. On a brighter note, a new trade in building stone was growing. When the railway arrived in 1840, they began moving the building stone in vast quantities, taking some of the trade from watermen working on the navigation. In the years around the mid 1840’s, the railways moved 30,000 tons of stone per year from the Halifax area alone. The quality of the local stone meant that there would always be a market for it and in recent years we have seen some of the old quarries that have been closed for decades, reopening again as the desire to use this great product continues.

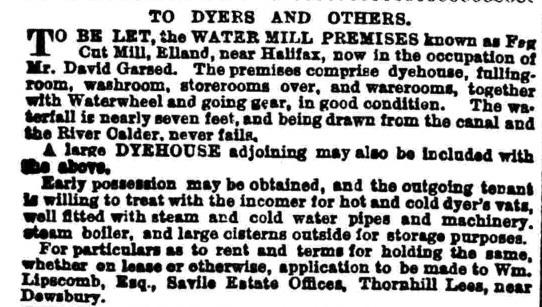

Looking again at the above 1893 map of Tag Cut and the Calder Fire Clay works you will see Tag Cut Mill situated on the northern side of the canal. Old maps show that a weir had been on the River Calder since the mid 1700’s, adjacent to where the power station once stood therefore one can assume that a water mill must have been located in the area at that time.

Tag Cut Mill was certainly there in the mid 1800’s but despite being used for different activities, its fortunes never prospered. It was located on an area of land between the river and the canal therefore a bridge was necessary to gain access from both sides. There is no evidence that a bridge existed across the river from the turnpike road we now know as Elland Road. When plans for the Manchester & Leeds railway were put forward in the late 1830’s, it was considered necessary to create a bridge under the railway, which still exists and leads across to Old Earth and the bottom of Lower Edge Road. Without this bridge, the mill would have been effectively marooned.

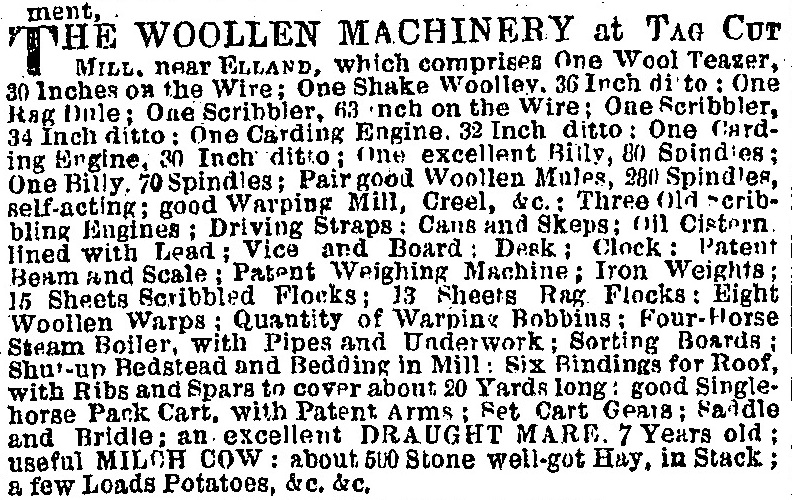

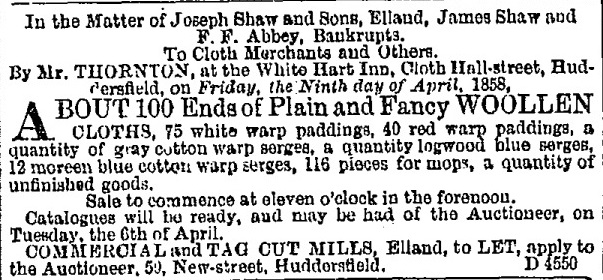

An advert in the Leeds Mercury from 1847 shows that Tag Cut Mill had been used for woollen textile production but when the business failed, the equipment was auctioned. This included a milch cow, a seven year old horse, a stack of hay and a few loads of potatoes.

In 1858 there was a further auction when the business of Shaw, Shaw and Abbey was declared insolvent. In 1878, David Gased’s dyeing business also failed and in the 1880’s, gas engineers, Greenwood & Darwin experienced a similar outcome. Was it because of the location that the occupants of Tag Cut Mill suffered the same fate, time after time? What is certain is that by 1907, the mill had been demolished. Looking at that area today, alongside the existing weir, you would never have thought that a large mill was once located there.

At the western end of Tag Cut is an old packhorse bridge which is currently in a poor state of repair, surrounded by weeds and bushes. The bridge used to be very important as it was the only way to cross the canal and gain access to Tag Cut Mill from Rastrick and the Lower Edge region.

The land between the river and canal was very fertile and was used to graze sheep and cattle and grow crops therefore access was needed for that also. It was at this location that barges entered and exited Tag Cut from the River Calder which once again became navigable at that point. The river continued towards Elland before a further section of canal took river transport in the direction of Salterhebble and then onward to Sowerby Bridge.

The western entrance to Tag Cut is on a bend in the river and during times of flood, the water pressure would have been immense upon the lock gates. It was important that the gates were closed during such events in order to prevent the devastation we have previously discussed in those conditions.

Closing the flood-lock gates in times of flood would make the canal a safe haven for the barges, so it was important that they were strong and well maintained. The carved stone grooves where the huge gateposts were once fixed can still be seen today by the old packhorse bridge.

During the 1950’s, a resident of Lower Edge, Fred Craddock built a wooden jetty at the entrance to the packhorse bridge and from there, he hired rowing boats to members of the public. There are still people around to this day who fondly remember ‘Craddock’s Subs’ as they were affectionately known. This was due to the fact that most of the boats leaked and along with the oars, the rowers were issued with a ladle can to empty the water out thus preventing your feet from getting wet.

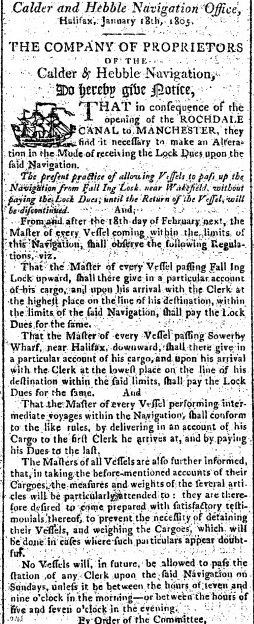

I have previously mentioned that in 1770, the navigation had arrived at Sowerby Bridge from the east. The ambition of the canal owners was to eventually connect with the Rochdale Canal at that location. This would in turn link with other waterways and form a direct connection over the Pennines to Manchester and eventually out to the western port of Liverpool. Plans for the Rochdale Canal were first discussed in 1767 but events such as Britain’s war with America, hindered that progress. The link wasn’t completed for over 37 more years at which point the Calder & Hebble Navigation, travelling through our tiny section of Tag Cut, formed part of the M62 motorway of its day. In the January of 1805, this canal was the only direct link between the east and west coast ports.

The only other two canals that eventually did this were the Huddersfield Narrow and the Leeds – Liverpool canals. The Huddersfield Narrow wasn’t completed until 1811 whilst the Leeds – Liverpool wasn’t completed until 1816 despite commencing work in 1774.

I suspect that it was because of the importance of the route in 1805, following the opening of the Rochdale Canal to Manchester that plans were made to build a further extension to the Calder & Hebble Navigation. The ‘new’ section of canal that we now know, which travels from Brookfoot, was started in 1805 and concluded in 1808. This created the current canal which extends from Brighouse to Salterhebble and then on to Sowerby Bridge and beyond, thus eliminating any need to use the unpredictable river.

Tag Cut, after 38 years of being part of a major canal network, was relegated to an arm of the main canal though it was still an important link for the quarrying that took place in the Rastrick hillside. If you search for Tag Cut on the internet, you will see many references to it having been built and then never been used. Where this theory started I do not know but many other websites and books have written the same but I will argue that they are all wrong. Tag Cut should be remembered as an important link in one of the earliest canal routes. It is slowly crumbling as nature takes over but I live in hope that one day, money will be found to restore the packhorse bridge before it collapses and is lost forever.

If you would like to see more historic photographs of the canal and Tag Cut area, why not visit my page entitled Historic Photographs of the Canal between Brighouse and Elland by clicking on this link:-