A SHORT WALK - GANNY LOCK TO BROOKFOOT

A PLEASANT WINTERS DAY WALK ALONG THE CALDER & HEBBLE NAVIGATION WITH A LITTLE BIT OF HISTORY THROWN IN

INTRODUCTION

This is a short walk along the canal which I took with Floyd, the Border Terrier on Tuesday 15th December 2020. It is very pleasant and steeped in history but if you want to know more about that, I have added a link at the end which will take you to the relevant page on this website. I can get away with putting this walk onto a Rastrick website because part of Brookfoot was actually within the Rastrick boundary up until the early 20th century. The pictures will be recognisable to many of you but if you have never ventured onto the canal towpath, it is worthy of a visit and is mainly wheelchair/mobility scooter friendly.

The month after these photos were taken, the River Calder flooded. Not an unusual occurrence only this time, the pressure of the water was too great and the ancient weir at Brookfoot collapsed in the centre section. It had previous held back water to a depth of around 1.5 metres (5 feet) but as the water drained away, new features appeared in the river, that hadn’t been seen for many years.

There is a link at the end of this story which will take you to another page on this website, where photographs of the weir collapse can be seen.

I parked my car at Bank Street and walked up to the end of the road where a path takes you down to Ganny Lock, passing beneath a huge stone wall (above) onto of which is a house, built on the hillside in 1867. It fronts onto Elland Road and was the Vine Hotel before it lost its licence in 1933 .

The navigation reached Brighouse in 1764 and was then extended to Salterhebble and then on to Sowerby Bridge where it linked with the Rochdale Canal. When the latter was opened, it completed an east coast to west coast link. You could call it the early 1800’s version of the M62 motorway.

In order to keep costs to a minimum, the designers used the river wherever possible but in some places it was impossible to pass by boat. Examples of this are where the river bed was solid rock and the water quite shallow or where weirs had been built to create a head of water which then drove the water-wheels in water powered mills. In order to navigate these obstacles, cuts had to be made around them. Some were not very long, hence a ‘short cut’, a term that we still use to this day. Two such weirs had been in existence on the Calder at Brighouse (and are still there) and so a canal had to be built to by-pass them. The canal ended at a place known as Ganny where it returned back into the river before entering a second cut across the low lying fields below Lillands in order to by-pass yet another weir which drove the waterwheel at Brookfoot Mill. In later years, the canal was extended from Ganny to Brookfoot and the lock-keepers cottage at what we now know as Ganny Lock was the point where the old canal re-entered the river.

The section of canal between Ganny Lock and Brookfoot was constructed in 1780. It was deemed essential because of the constant flooding in the fields below Lillands. Huge damage was caused during major floods, when the raised walls of the canal were swept away by the deluge coming down from the Calder Valley. Due to the land sloping downhill from Brookfoot to Brighouse, it was decided to keep the new cut on the same level as the river at Brookfoot. This meant hewing out the solid rock hillside below Elland Road resulting in the canal being much higher than the river as it meandered down to Ganny Lock. In theory, it meant that the canal would never flood because a section of the towpath was made slightly lower at a point near to Ganny Lock. This meant that any flood water could run off the canal and through the above wall, which had been especially designed to allow the water to cascade down into the river below. Of course, we all know that it failed on Boxing Day 2015, such was the torrent of water that came downstream that day.

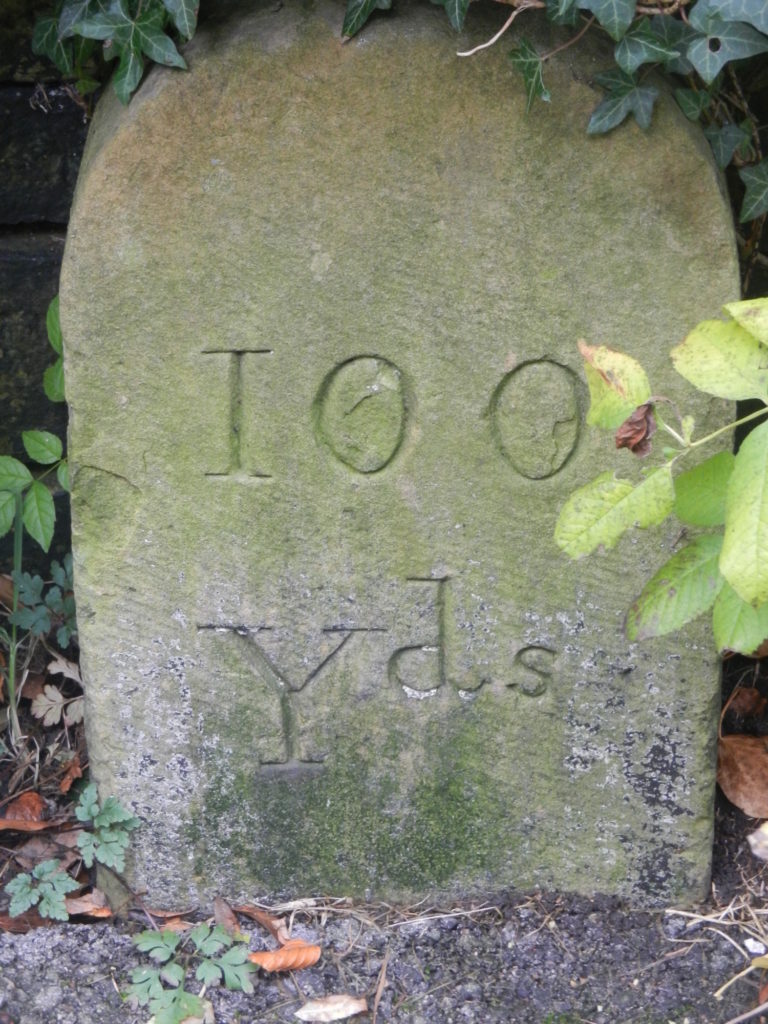

For those who remember the days of ‘pea-souper’ fog, when visibility could reduce to a couple of metres in front of you, imagine being in charge of a horse that is towing a canal barge laden with thirty-five tons of Elland flagstones. You are guiding your horse along the towpath when suddenly, a lock gate becomes visible in front of you. It would be impossible to slow your barge down before it collided with the gates causing massive damage. The Calder & Hebble Navigation Company therefore placed markers beside the towpath, warning the bargee that a lock was just ahead. The photograph below shows one these markers close to Ganny Lock.

It was at this exact spot that in July 1881, a boat owner named Sam Schofield was guiding his towing horse at 10 o’clock in the morning when he saw a basket, a satchel, umbrella, a woman’s hat, a child’s hat and a child’s collar and jacket laid carefully against the wall at the side of the marker.

Jane Hill, a 22 year old woman from Brookfoot had earlier been seen walking along the towpath with her 2 ½ year old son, Alfred. Jane was seven months pregnant and was worried about having another child. Sam moored his barge at Ganny Lock and made his way to the local police house where he reported the matter to PC Charles Chilvers who came to the scene and took possession of the property. He then arranged for the canal to be dredged at this point and the bodies of Jane and Alfred were recovered.

At the inquest held at the Woodman Inn, Brookfoot, the verdict of the wilful murder of Alfred by his mother was returned whilst a verdict of ‘drowned herself while in an unsound state of mind’ was returned on Jane. Ever since I first discovered this story, I always think about Alfred and Jane as I walk past this spot.

Walking along the towpath to Brookfoot you can hear the murmur of traffic above the hillside to the right where the road runs between Brighouse and Elland. The field to the left of the river was where the canal used to travel before this section of canal was built, in order to by-pass the weir at Brookfoot Mill.

Looking back towards Ganny Lock, this photograph above shows the solid rock face of the hillside from which this section of canal was hewn. Steel, dynamite or gelignite hadn’t been invented when this work was carried out and the navvies, so called because they worked on the navigation, were mainly Irish labourers and had to toil in all weathers with iron chisels, crowbars, hammers, spades and wheelbarrows after the initial blasting with black powder. Their tools were blunted very quickly and an army of blacksmiths would have followed the workers as they made progress down the valley.

Approaching the bend in the river and canal, the Red Beck flows into the canal having travelled down from Shibden and through the Walterclough Valley. The name derives from the colour of the water which runs over sandstone and mudstone, rich in chemical elements such as iron which becomes soluble in certain conditions. This produces iron oxide, probably better known as rust, which in turn taints the colour of the water.

One private entrepreneur had plans drawn up in the 18th century which, if they had come to fruition, would have seen a canal across that valley, capable of providing transport for the raw materials and finished products connected with the textile mills of Halifax. It’s a pity that it didn’t happen really as a towpath walk from Brighouse to Shibden would have been an excellent addition.

In times of heavy rainfall, the Red Beck can deposit vast amounts of water into the canal therefore, immediately opposite the beck is another overflow where excess water can freely flow down a cobbled slipway into the river below. The Red Beck would have flowed naturally into the river until the canal dissected it and created this confluence.

This clever design meant that there would always be sufficient water in the canal, even when the lock gates were opened regularly by passing barges. It also ensured that any excess water would still flow into the Calder and help to keep the waterwheels moving in the mills downstream, much to the delight of the mill owners.

After negotiating the bend, the towpath heads towards Brookfoot in a straight line but by sneaking between the trees and a fence belonging to the Avocet company you come to Brookfoot Beach ! This is a section of the river just below the weir and when the waters subsided following the Boxing Day flood in 2015, a sand and pebble ‘beach’ was left behind. It is also interspersed with bits of broken 19th century ceramics that have been washed out of an old tip further upstream.

From this point, there is a view across the fields towards Lillands and Brighouse and the ancient weir that once held back the water to drive the grinding stones of the old Brookfoot Corn Mill, is a short walk away along the river bank. As mentioned at the start, the weir was swept away in a flood in January 2021, more details about that are available at the end of this story.

On one visit this last summer, there was even a family with Mum, Dad and two children playing in the river with inflatables and towels laid out on the beach. Other teenage kids were sat on top of the weir with the boys doing heroic things in the water, trying to impress the girls. Not something that is advisable when the river is in full flow.

The towpath then heads up to Brookfoot, past the modern Avocet warehouse and to the old Brookfoot Mill. It’s hard to believe that this piece of land between the river and the canal was the site was a cricket ground and tennis courts from the late 1800’s until around the time of the 2nd World War. Brookfoot was a thriving little community with its own school and church, three public houses and plenty of work within a short walking distance. Alas, just about everything has gone except for the various industrial workshops.

It is also difficult to appreciate that the canal banking on the left hand side of the waterway was once a busy wharf. Fixed cranes ran along the length of the wharf which would load and unload the cargo from the barges. Originally owned by the Freeman’s, who were a Southowram stone quarrying family, Brookfoot wharf was an important loading area for stone that had been quarried on the hillsides of Southowram. It also served the huge mill on the bend in the road at Brookfoot which later became known as the Bradford Dying Association or just B.D.A.. It wasn’t just stone that came into the wharf as coal was brought upstream from the eastern coalfields as local factories and houses were all in need of this once essential product.

It was at Brookfoot where the old 1780 section of canal re-entered the River Calder having travelled up from Brighouse. From there, barges headed upstream towards Elland, Halifax and Sowerby Bridge via Tag Lock. The ‘newer’ section of canal that goes through Elland and on to Salterhebble and Sowerby Bridge was built between 1808 and 1811. The old lock into the river continued to be used for many years after the new section of canal was constructed. This was because barges still needed to move stone from the quarries at Lower Edge, Rastrick. The stone was brought down through the woods on wooden carts via delvers tracks, many of which are still visible today. The textile mill at Tag Cut and the Fireclay Works, which later became the brickworks, also used canal transport but when they closed, Tag Cut ceased to be used and the entrance into the river was closed for good in the 1960’s. The land between the lock gates and the river was filled with rubble and it is only a matter of time before the gates succumb to nature and disappear forever.

The delvers track on the photograph below was used by the delvers who brought stone down through the woods from the quarries at Lillands and Longroyd. A small wooden wharf was positioned along the edge of the river at the same angle as the track. This meant that the cumbersome wooden carts could be driven straight onto the wharf to be unloaded, with minimal effort involved in manoeuvring the heavy vehicles. During dry summers, remnants of the posts that carried the wharf can still be seen protruding from the river.

The photograph below is taken at Brookfoot, looking up the river towards Tag Cut and Elland. Strangstry Wood, also known to some as Reins Wood or Lillands Wood is on the opposite banking, leading up towards Rastrick whilst the hugely popular Cromwell Bottom Nature Reserve lies between the river and canal just a little further upstream.

When the ‘new’ section of canal from Brookfoot to Elland opened in 1811, the towing horses had to cross over two bridges in order to remain on the towpath which only ran along one side of the navigation. The cobbles were a popular way of surfacing roads at that time and they were easily obtained from the many quarries in this area. If you look closely at the end of the bridge on the left hand side, you will see the scoring marks in the stone. These were made over many years by the tow-ropes as the horses positioned the barges into and out of the lock below.

This photograph below shows the Brookfoot bridge from tow-path level. It is still looking as solid as the day it was built, two hundred and ten years ago.

The next two photos are taken from the bridge, looking in both directions. Facing towards Brighouse, the old Brookfoot Mill dating from 1865 can be seen on the right with Camms Bridge approx. 150m downstream. The name of Camm has stuck with the bridge since William & Alfred Camm opened their spinning business at Brookfoot Mill in 1868. Other occupants over the years have been Turner & Wainwright (toffee manufacturers), Meredith & Drew (confectioners) and Kossett Carpets but it is now occupied by Avocet (hardware manufacturers).

The Brighouse Angling Club now owns the fishing lakes beside the Brookfoot Lock area. These were former gravel pits that closed when another of the many floods that have hit this area over the years, filled the deep pits with water. The owners decided that it would be uneconomical to drain them and continue the work. They were subsequently sold to not only create the fishing lakes but also the nearby waterski club.

As I said at the beginning, there are other pages that go into more detail about the Calder & Hebble Navigation and Tag Cut so if you wish to read a bit more and see some historic photographs and maps, just click on the text below and it will take you to the relevant page.