FROM CLIFTON TO MT. EVEREST

THE STORY OF MAURICE WILSON, A 1st WW HERO WHO DESPITE HAVING NEVER FLOWN IN HIS LIFE, BOUGHT AN AEROPLANE TO FLY TO MT. EVEREST IN AN ATTEMPT TO BECOME THE FIRST PERSON TO CONQUER THE MOUNTAIN BUT CRASHED IN A FIELD AT CLIFTON BEFORE SETTING OFF.

INTRODUCTION

The story of Maurice Wilson could have come from one of the adventure comics of the 1930’s which portrayed amazing heroic deeds of derring-do by pioneering men of the day. One such comic character was Ace Drummond, an aviator who flew to the trouble spots of the world to defeat the tyrants of the day. He first appeared in newspapers in 1933 but unfortunately, he was a fictional character created by Eddie Rickenbacker. A real-life Ace Drummond could have flown to Germany at that time and sorted out Chancellor Hitler before he went on create mayhem around the world

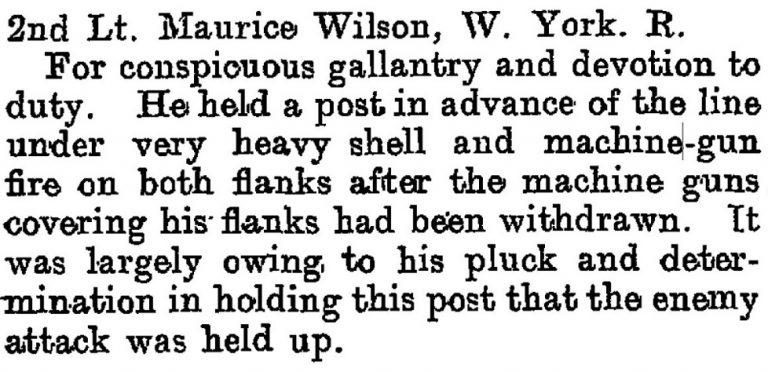

Maurice Wilson was born in Bradford on the 21st April 1898. He joined the Army in 1916 as a commissioned officer and served with the West Riding Regiment in the horrendous battle at Passchendaele. As a 2nd Lieutenant he was awarded the Military Cross for his brave actions at Meteren where he single-handedly held a machine gun post against a German attack, whilst every other member of his unit had been either killed or wounded. His citation read:

Wilson was later wounded by machine gun fire and he carried discomfort around in one arm for the remainder of his life. He also witnessed the torment of one of his brothers suffering greatly from shell shock which turned the unfortunate chap into an emotional wreck. Wilson sought compensation for himself and his brother, but his claims were constantly snubbed which resulted in him developing a loathing of authority and officialdom.

Like many other veterans of the Great War, Wilson found it difficult to settle into normal life at the end of the hostilities and it is more than likely that he was suffering with depression. He married in 1922 but he became restless and yearned for adventure. His father had died in 1921, leaving estate valued at today’s equivalent of just under £1m. Wilson and his wife soon began to lead separate lives as marriage had failed to settle him. He felt the desire to travel and with the money inherited from his father, he wandered around the globe with little consideration for either the women or the jobs that he became involved with and which he cast aside as and when it suited him. His wife was certainly still alive in 1926 and there is no evidence of a divorce but this didn’t stop Wilson from marrying for a second time whilst visiting New Zealand. That marriage also failed, and Wilson once again set off on his travels. In 1932, he found himself sitting in a café in Freiburg, Germany where he read a magazine article about the 1924 British Everest Expedition in which George Mallory and Andrew Irvine lost their lives. There is still debate to this day as to whether the pair fell on the way back down after reaching the summit, or whether they were still ascending the mountain when they reached their tragic end. It was a classic tale of British heroism like that of Robert Falcon Scott and Ernest Shackleton, attempting to overcome incredible odds whilst striving towards an almost impossible goal. The image of such pioneers portrayed the greatness of the Empire and it appealed to Wilson considerably. He was going to become the first man to climb Everest and despite having no experience whatsoever, that was not a deterrent. He was determined to make the British people sit up and take notice of him.

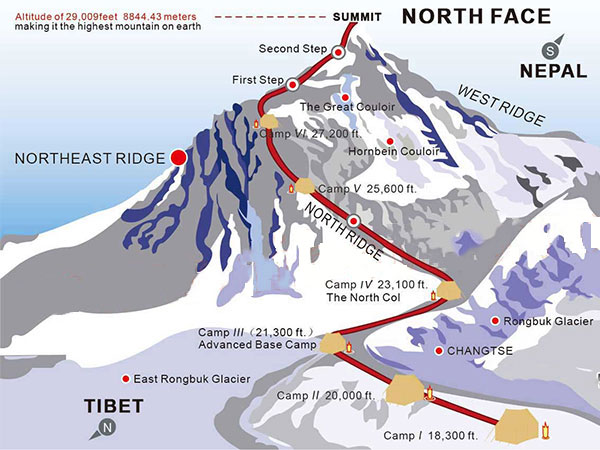

Having been beaten in the race to reach the North and South Poles, British explorers were determined to be the first to reach the top of the world and conquer Everest. Previous experienced climbers had been greatly assisted by local barers who not only knew the area but also carried their huge supplies and equipment but despite this support, no-one had ever made it to the summit. Some had met their deaths in the appalling weather conditions which prevail upon the mountain, where blizzards and avalanches are quite typical, yet Wilson was not discouraged and concluded that he could still make it to the summit single-handed. He was going to do this by preparing his body with the power of prayer and by fasting. He claimed that he had met a man in London who had healed many people from illnesses which doctors had deemed incurable, purely by adopting this technique. Wilson’s original plans were to purchase an aircraft from which he would parachute onto the mountain and then simply climb to the summit.

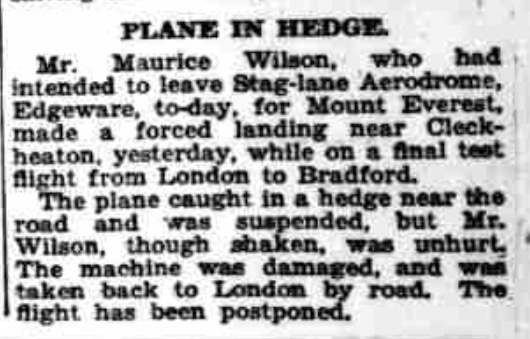

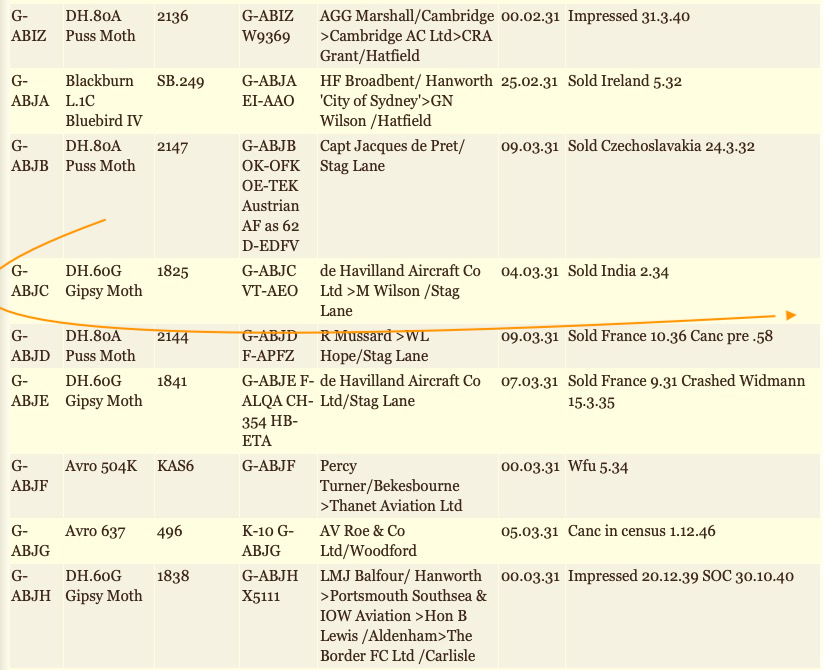

Upon his return to England, Wilson became a member of the London Aeroplane Club at the Stag Lane Aerodrome, Edgware, London. He bought a Gipsy Moth DH.60 bi-plane on the 22nd February 1933 which was a two-seater aircraft consisting of a wooden framed fuselage, covered in plywood and fabric. This was exactly the same make and model of aircraft in which Amy Johnson had made the first ever flight from England to Australia in 1930. Its registration number was G-ABJC and was built by De Havilland Aircraft Company who were also based at the Stag Lane Aerodrome. Some reports state that the aircraft bought by Wilson was first registered in 1925 but I suspect that this may be to dramatize the story by suggesting that Wilson bought a clapped-out old aeroplane. I have found that it was actually registered in March 1931, therefore making it just under two years old. It had been used by the famous Sir Alan Cobham’s Flying Circus which toured the country at that time with their daring aerobatic display team (pictured below on the top of the four plane stack, pictured with the permission of Historic England). Wilson paid for flying lessons and in less than two months, he was able to fly off in his own aircraft. He christened the aeroplane Ever Wrest.

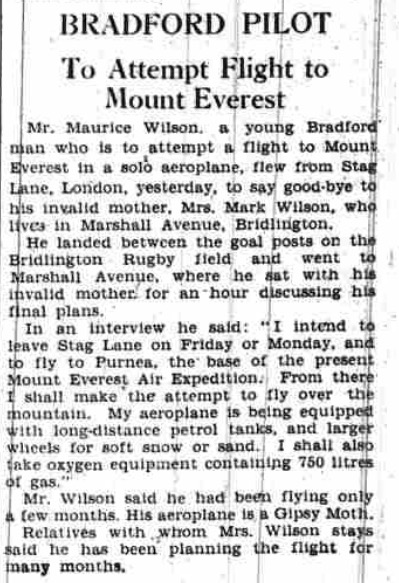

In the Yorkshire Post newspaper dated the 20th April 1933 (below), it was reported that Wilson flew from the Stag Lane Aerodrome, Edgware, London which was owned by the de Havilland Aircraft Company to Bridlington in East Yorkshire. He landed his aircraft on the local rugby field before walking less than one mile to Marshall Avenue, to say goodbye to his invalid mother who lived there.

The location of that crash was actually in a field adjacent to Highmoor Lane, Clifton. My grandparents lived at Thornhills, Clifton at the time and my grandfather, Fred Eccles, was a keen amateur photographer. During the ‘depression years’, he used to go to the Isle of Man during the summer months and find work in Douglas hotels. He also worked as a part-time promenade photographer to fund his love of cameras and it is for this that I now have so many old family photos from the 1920’s and 30’s.

My grandfather quickly heard of the aeroplane accident, which was just over the fields from where he lived. He made his way up to the scene of the crash, armed with one of his cameras and he took two photographs of the damaged aircraft which are shown here. I have read several reports about the crash and as far as I am aware, these are the only existing photographs of the scene that day. On one of the photos the registration G-ABJC can be clearly seen on the side of the Gipsy Moth aircraft. This registration is confirmed on the below list of registered aircraft and shows M. Wilson / Stag Lane as an owner but shows the date of registration as the 4th March 1931, not 1925 as is reported in many stories about Maurice Wilson.

Following Maurice Wilson’s declaration that he was going climb Mt. Everest and plant a Union Jack flag upon the summit, he was criticised and occasionally mocked by the press and especially the mountaineering establishment. The Alpine Club was established in 1857 in London and along with the National Geographic Society, they were both very much linked with former military and government personnel. They wanted the first person who conquered Everest to do it for the glory of the nation, not for personal fame but more importantly, they should be a member of the elite Alpine Club. The societies looked upon Wilson’s attempt with a certain degree of contempt and would not endorse or encourage his quest. Wilson didn’t exactly endear himself to the hierarchy of these clubs as his training to conquer the world’s highest mountain consisted of a few hikes in the Lake District. They thought that Wilson was treating ‘the ultimate challenge’ with contempt. Nevertheless, Wilson was getting plenty of publicity in the press and he became loved by the general public but reviled by those in authority. After having his Ever Wrest plane repaired following the crash at Clifton, he finally set off on the 21st May 1933 despite being forbidden to do so by the Air Ministry

Wilson had a larger fuel tank fitted but his Gipsy Moth was still limited to around 620 miles on a full tank and so his route to Everest required some serious planning. He flew from Stag Lane Aerodrome to Freiburg, Germany, where he first had the idea of this adventure. From there, he flew to Passau on the Austrian border but had to abandon his plans to cross the Alps from there due to the poor weather, so he headed back to Freiburg and went over the Western Alps to Rome where he was greeted by a large and excited crowd. These were the days when heroic pilots were testing new boundaries in aircraft flight and their stories filled the columns of newspapers, magazines and boys comics, all around the world. After resting for a few days, Wilson headed across the Mediterranean towards Tunisia but he encountered complete cloud cover whilst over the sea. Unbelievably, this was the first time he had flown in cloud but somehow, he managed to successfully negotiate his way through it. Within a week of departing from London, Wilson had reached Cairo and from there he headed for Baghdad. The newspapers were full of admiration and Maurice Wilson was the talk of the nation, hitting the headlines of not only the tabloid newspapers but even The Times carried his story at regular intervals.

Wilson had planned on flying over Persia and then onto Nepal or Tibet but permits were required to fly over these countries. Previous expeditions had relied on diplomats from the British government to sort out the required paperwork but because Wilson didn’t have the backing of the British government, he could not expect any assistance or favours from them. Whilst in Baghdad, Wilson had to change his plans once again, but he didn’t have any maps for his new route. He resorted to referring to a child’s atlas to plot his next stage before heading off for Bahrain, 620 miles away. It was mid-summer with extremely hot weather and Wilson was lucky to make it to his destination before he ran out of fuel.

Whilst in Bahrain, Wilson once again had obstacles placed in front of him by the British government who told the Bahraini government not to allow him to re-fuel. He was ordered to attend at a local police station where he was told that he could travel no further as the only forward re-fuelling places within the range of his aircraft were in Persia, a country into which he was forbidden to fly. Wilson agreed to return to Baghdad if he could be permitted to re-fuel but whilst in the police office, when no-one was watching, he managed to scribble some quick notes on the back of his hand from a map that was on the wall. The following day, he set off from Bahrain but instead of returning to Baghdad he headed east, over the Persian Gulf towards Gwadar, India (now in Pakistan). This was fraught with danger as the journey was 745 miles, way beyond the range of his aircraft but somehow Wilson managed to make it after nine hours of continuous flying. He arrived just as the sun was setting and with his fuel gauge on zero. We must remember that he was flying only by a compass and the occasional feature on the ground below. If he had still been still in the air when darkness fell, he would have had little chance of reaching his destination. He even managed to overcome a complete stall of his engine at one point. As some commentators said at the time, if he was capable of overcoming these difficulties, could it be just possible that fortune was with him and that he may be successful with his quest to climb Everest.

After giving his aircraft engine a well-earned rest in Gwadar, Wilson flew on to Karachi where he arrived on the 2ndJune, twelve days after leaving London but by the 5th June, the Daily Mirror reported that he was having problems in reaching his destination because the Nepalese government wouldn’t allow him to fly his aircraft into Nepalese air space. He told the Reuters news agency that if forced to, he would abandon his aircraft on the border and hike to Everest.

By the 10th June, there was still no more news from the Nepal and the Yorkshire Post reported that Wilson was now planning to fly to Kathmandu from where he would walk the remainder of his journey on foot. Although the Indian authorities had technically taken charge of his Gipsy Moth, he was still allowed to fly around India and he seems to have done this on a regular basis whilst trying to get approval to fly into Nepal. Despite many efforts to revert this decision, Wilson was fighting a losing battle, especially as he didn’t have the backing of the British government and he was once again forced to revise his plans. Having flown to Purnea, the Halifax Evening Courier dated 4th July 1933 reported under the headline: TO ATTEMPT EVEREST ON FOOT – AIRMAN NOT ALLOWED TO FLY, ‘Maurice Wilson, the airman who has come to make an attempt on Mt. Everest, left Purnea today, after vainly trying to persuade the Maharajah of Nepal to fly in the region of the mountain. It is believed that he plans to lay up his aircraft at Hathwah, Nepal and proceed with his plan to scale Everest on foot, since he is not allowed to use his aeroplane.’ The Nepalese responded by not only refusing Wilson permission to fly to Mt. Everest but they put a ban on him from flying anywhere in that country. Even worse was to follow as a further communication informed him that in addition to the flying ban, he was not allowed to even hike through Nepal to Everest or climb the mountain from the Nepalese side.

Newspaper reports then began to filter back to England of rumours that Maurice Wilson had gone missing. During his flights around the north of India, Wilson had mysteriously disappeared when flying to Lucknow on the 6th July. Had he ignored the Nepalese and flown to the Everest region, had he crashed in some remote area? Nothing was heard of him for over a week and people began to worry about his fate but then he suddenly turned up on the 14th July, explaining that he had been forced to make an emergency landing because of poor weather and had been the guest of a British official for a week in Bihar Province.

Once the realisation that the Nepalese were not going to change their minds about him being allowed into their country sank in, Wilson formulated yet another scheme. He had come so far and was not going to give up so easily therefore, undeterred, he remained in India. He made his way to Darjeeling, close to the eastern border of Nepal but his new plan was to enter Tibet from the north of India and go around to the Tibet side of Everest from where he would climb the mountain. When the Tibetan authorities found out, like the Nepalese, they also refused him permission to enter their country. This makes me wonder if the ‘old boys club’ within the British government and the Alpine Club had any influence on these decisions, such was their opposition to Wilson’s attempt the climb. He was forced to spend the winter in Darjeeling and to pay for his expenses, he sold his Gipsy Moth aircraft to Mr. R. H. Cassell on the 23rd December 1933

Over the winter, Wilson kept himself out of the news as he laid low in Darjeeling, hoping the authorities would forget about him. He would need assistance to get to Everest through Tibet and managed to contact three Sherpas who had worked on previous Everest expeditions as porters. Wilson and the three Sherpas left Darjeeling disguised as Buddhist monks on the 21st March 1934. Wilson pretended to be deaf and dumb and in weak health to avoid suspicion and they camped in valleys rather than mountain villages to evade detection. After a 24 day trek, they arrived at the Rongbuk Monastery on the 14th April, with the mighty Everest right in front of him. It is the highest monastery in the world at 5,009m (16,434 feet) above sea-level and was a regular calling point for expeditions during the 1920’s and 30’s. Wilson was given equipment that had been left behind by the team led by Hugh Ruttledge in 1933. That team had failed to reach the summit by less than 900 feet. After staying at the monastery for just two days, Wilson left his porters behind and set off all alone to scale the mountain before him.

Wilson kept a diary of the events that followed and he wrote of how he found trekking up the Rongbuk Glacier very difficult. This is hardly surprising as he had never set foot on a glacier in his life. He lost his bearings and had to re-trace his steps on several occasions. He even threw away a set of crampons that he found at an abandoned camp as he didn’t think he would need them, something he would later regret. The weather became very poor and after five days he was still two miles short of Hugh Ruttledge’s Camp III below the North Col. He decided that he would have to return and wrote in his diary, “it’s the weather that’s beaten me – what damned bad luck.”

He arrived back at Rongbuk Monastery four days later, suffering from a twisted ankle, snow-blindness and he was also in immense pain from the wound he sustained during the war. On the 12th May, after eighteen days of recuperation, Wilson set out once again but decided to take Sherpas Tewand and Rinzing with him. The Sherpas had previous experience of the glacier and with their expertise, Wilson was able to make it to Camp III in just three days. Once again, adverse weather conditions prevailed and the group had to stay put for several more days which gave Wilson the chance to consider the best way to the summit from there.

He was fully aware of the ice slopes ahead and had at first considered taking a short cut to Camp V, thereby missing out Camp IV. He commented in his diary that by taking this shorter route, he would have to cut his own ice steps whereas if he took the longer route via Camp IV, there was a possibility that steps cut into the ice by previous expeditions and a hand rope would still be there. He once again set out alone, leaving the Sherpas behind at Camp III but on the 21st May, he reached the ice slopes only to find no trace of the hand rope or any ice steps. He made another attempt to reach the North Col on the following day but was beaten by an ice wall which was forty feet in height and proved impossible for him to climb.

Wilson returned to the Sherpas at Camp III who quite rightly advised him to give up on his plans as they feared going any further was one step too far. They begged him to return to the monastery with them, but he refused. He wrote in his diary “this will be a last effort, and I feel successful,” and so Wilson headed off once again on the 29th May. The writing in his diary was becoming worse (it wasn’t that good to start with) and it seems obvious that this once super-fit man was wearying rapidly. He camped at the base of the North Col because he was too exhausted to attempt it that day. The following day he wrote, “Stayed in bed all day,” but on the 31st May, he seemed a bit more upbeat as he wrote, “Off again, gorgeous day.”

Wilson had asked the Sherpas to wait for him for ten days as he anticipated that was the maximum length of time that it would take him to reach the summit and then return to Camp III but Tewand and Rinzing went back to the monastery where they waited for a further three weeks, but Wilson did not return. They made their way back into India and upon arriving at Kalimpong in mid-July, they made their story known.

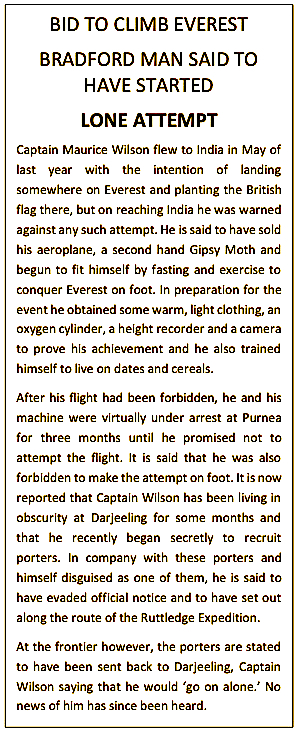

As the information reached the newspapers, reports such as this one on the left began to filter back to England as rumours abounded that Maurice Wilson was missing once again. Dated the 18th July, it read:-

Captain Maurice Wilson flew to India in May of last year with the intention of landing somewhere on Everest and planting the British flag there, but on reaching India he was warned against any such attempt. He is said to have sold his aeroplane, a second hand Gipsy Moth and begun to fit himself by fasting and exercise to conquer Everest on foot. In preparation for the event he obtained some warm, light clothing, an oxygen cylinder, a height recorder and a camera to prove his achievement and he also trained himself to live on dates and cereals.

After his flight had been forbidden, he and his machine were virtually under arrest at Purnea for three months until he promised not to attempt the flight. It is said that he was also forbidden to make the attempt on foot. It is now reported that Captain Wilson has been living in obscurity at Darjeeling for some months and that he recently began secretly to recruit porters. In company with these porters and himself disguised as one of them, he is said to have evaded official notice and to have set out along the route of the Ruttledge Expedition.

At the frontier however, the porters are stated to have been sent back to Darjeeling, Captain Wilson saying that he would ‘go on alone.’ No news of him has since been heard.

The following day, as the reality of the situation became more clear, the first announcements were made that Maurice Wilson had almost definitely met his death on Everest . The LEEDS MERCURY (left) carried the story which was repeated in newspapers around the world.

Leeds Mercury – 19th July 1934

ALONE ON MOUNT EVEREST – BRADFORD MAN FEARED DEAD

It is feared that disaster has overtaken Captain Maurice Wilson who recently set out alone to climb Mount Everest.

The chances that Captain Maurice Wilson is still alive are very slight. This former British officer attempted to conquer Mount Everest single-handed and he appears to have paid for his temerity with his life.

The porters who accompanied Captain Wilson on his journey state that they had accompanied him as far as the Rongbuk Monastery in Tibet, three miles from the old base-camp. Accompanied by only two porters, Captain Wilson then went as far as Camp III, where he asked the men to wait ten days until he returned.

He went off alone, carrying a small tent, an ice-axe, some kit and a camera. He was last seen nearing Camp V. The porters waited for three days at Camp III and then returned to the Monastery, where they waited for three weeks.

In 1935, Eric Shipton, who had been part of the unsuccessful Ruttledge Expedition of 1933 was back on the mountain leading a reconnaissance expedition for his own attempt at the summit in the following year. He recruited some Sherpas in Darjeeling, much the same as Maurice Wilson had done. One of his choices was a man called Namgyal Wangdi, who was volunteering his services as a porter for the very first time. This man later went under the name of Tenzing Norgay or ‘Sherpa Tenzing’ who of course shot to fame when he accompanied Edmund Hillary to the summit of Everest in May 1953. They became the first men to conquer the mountain after so many previous attempts had failed.

As Shipton reached the area below the North Col, he came across the body of Maurice Wilson, laying upon his side at the foot of the ice slope. Nearby were the remnants of his tent and a rucksack containing various personal articles including Wilson’s camera, diary and the Union Jack that he was so desperate to plant upon the summit of the mountain. It is assumed that he died of either starvation or exhaustion. Wilson was buried in a nearby crevasse and Shipton built a stone cairn to mark the grave but Wilson has refused to remain there as his frozen mummified body has re-surfaced no less than five times in the years 1959, 1975, 1985, 1989 and 1999.

Wilson’s diary was gifted to the Alpine Club and remains with them to this day but its content has created much debate over the ensuing years. In the Alpine Club Journal of 1965, T. S. Blakeney, the Assistant Librarian wrote, ‘He seems to have had no real interest in mountains or mountaineering; climbing Everest was just a job to be done, to establish to the world an article of his faith. There is no apparent reason why he should not have selected any other hard physical test, such as swimming the Channel. A stunt is only justified by success, and Wilson’s attempt on Everest remains a stunt.’

Returning to Clifton and the fields where Maurice Wilson crash landed on the day before he was supposed to embark upon his adventure which eventually cost him his life, several light aircraft had been known to have landed there previously and it soon became an identified landing site.

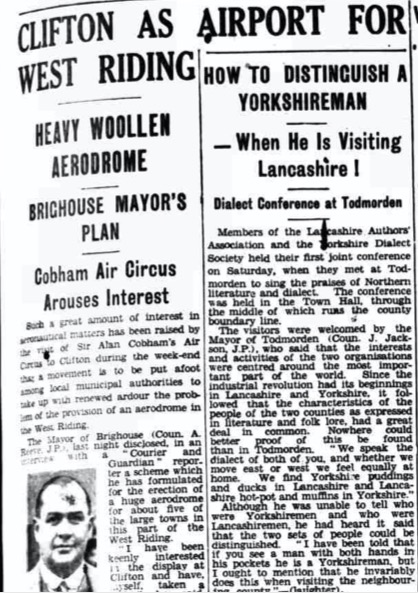

Ironically, just two days after Maurice Wilson lost his life on Mt. Everest and his frozen body laid in the snow beneath the North Col, Sir Alan Cobham’s Flying Circus, from whom Wilson had purchased his Gipsy Moth aircraft, held a successful air show in that very field in Clifton where Wilson had crash landed the previous year. It was held over the weekend of the 2nd and 3rd June 1934. The Halifax Courier reported that the Mayor of Brighouse, Councillor Arthur Reeve had formulated a plan for a West Riding airport at that location.

In the report, Cllr. Reeve stated that, “I have been talking the matter over with Mr. Eskell, the general manager of the air display, and we are convinced that Clifton would make an ideal place for an aerodrome for the big towns of the West Riding. My suggestion is that Halifax, Huddersfield, Bradford, Dewsbury and Brighouse should share the expense of an expert survey with the object of establishing an aerodrome in this large industrial area. If the site were agreed upon, and I am convinced that Clifton would be an admirable place, we could name the aerodrome the ‘Heavy Woollen Aerodrome’ It could be used as a centre for the whole of the West Riding industrial area.”

He went on say that he was going to put his suggestion forward to Brighouse Town Council at the earliest opportunity, adding that, “ I am convinced that we older folk do not always realise to the full extent the amount of flying that the younger generation is going to do. Trade always followed the development of waterways and railways and I believe that it will follow the airways. For instance, continental buyers will be able to come right into the West Riding within four or five hours by air.”

What foresight Mr. Reeve had but of course, the airport never happened.

The report upon the Flying Circus said that the weather had been excellent with good visibility and 50,000 people had watched the performances and 3,000 people had paid for flights in an aircraft. My grandfather was one of them ! Such was the interest that trips in the smaller planes such as the Gipsy Moths had been sold out before the event and only the odd seat was still available in the larger aircraft.

Flight-Lieut. Geoffrey Tyson performed some amazing stunts for the thrilled crowds that spread over adjoining fields all over Clifton. ‘Miss Joan Meakin demonstrated her glider which was towed to a great height by an aeroplane whilst one of the most sensational feats was the parachute descent by Mr. Ivor Pace from the wing of a large Handley Page airliner.’

The exploits of Maurice Wilson is a story that I think would make a great film. I will leave you to form your own opinion as to whether he was a maverick hero, a man suffering from a mental illness after his war exploits, a lost soul, gifted showman or any one of the many other ways that have been used to describe him, but Maurice Wilson and Sir Alan Cobham’s Flying Circus …. who would have believed the goings-on in the fields of Clifton in 1933 and 1934 !

This is a short two minute film on YouTube of Sir Alan Cobham’s Flying Circus in 1932 and gives you an insight into what people would have witnessed in the fields of Clifton a couple of years later.